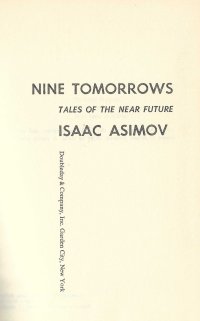

I actually started reading this before I started Nine Tomorrows by Isaac Asimov; after finishing another book, probably Red Snow and Death Had Yellow Eyes, I hit the stacks and the hardback Asimov collection caught my eye, so I read it instead of completing this collection, which underwhelmed me.

I actually started reading this before I started Nine Tomorrows by Isaac Asimov; after finishing another book, probably Red Snow and Death Had Yellow Eyes, I hit the stacks and the hardback Asimov collection caught my eye, so I read it instead of completing this collection, which underwhelmed me.

First and foremost, it is not a collection of science fiction stories. It seemed like the book was only a third science fiction, but a review makes it clear that it was not that little. The book contains:

- “The Kilimanjaro Device”, wherein a stranger in a time-traveling truck is seeking Ernest Hemingway, hoping to help him to a better death (the plane crash in Africa) than the one Hemingway eventually got.

- “The Terrible Conflagration Up At The Place”, wherein a group of locals decide to burn the lord’s house, but when they find him there, he convinces them in a roundabout fashion to not by asking that they keep the treasures and heirlooms safe after the house burns.

- “Tomorrow’s Child”, wherein a couple discover that new birthing technology has trapped their baby in another dimension–he only appears weirdly in this one–and although scientist cannot solve the problem yet, they can send the parents to join the child.

- “The Women”, wherein a man and his wife are at the beach, and something in the water calls the man, and the wife knows and tries to keep him from going into the water.

- “The Inspired Chicken Motel”, wherein a Depression I-era family stays at a motel with a chicken with the gift of prophecy, and the chicken gives them hope.

- “Downwind from Gettysburg”, wherein an actor named Booth shoots an animatronic Lincoln.

- “Yes, We’ll Gather At The River”, wherein the owners of buildings along main street on the highway spend the last night before the authorities open the new highway that bypasses their town.

- “The Cold Wind and the Warm”, wherein strangers visit an Irish town and inspire the locals to look at things differently.

- “Night Call, Collect”, an old man left on Mars as a young man after the rest of the population returned to Earth to fight in the atomic war keeps getting phone calls that he programmed into the system to keep himself company. After decades, he hates it.

- “The Haunting of the New”, wherein a wealthy but decadent woman invites a frequent visitor to the debaucheries at her manor because it burned, and she reconstructed it completely the same, but this new manor does not want the orgies to continue.

- “I Sing The Body Electric”, wherein a recently widowed man orders a robotic grandmother for his children, to help take care of them and to tutor them.

- “The Tombing Day”, wherein a town has to move the graves in a cemetary because the highway is coming through, so a woman has the coffin of a man, her beau, who died 60 years ago, brought to her house. She discovers his body perfectly preserved at 23, and she laments her own aging.

- “Any Friend of Nicholas Nickleby’s Is a Friend of Mine”, wherein a conman lodging in a boarding house on the prairie pretends to be Charles Dickens and pretends to write the author’s works using his photographic memory. Even after the ruse is discovered, a boy in the house wants to believe.

- “Heavy-Set”, wherein a mother worries about her 30-year-old son who is still at home and who avoids most social interactions even though people and girls invite him places–with incest only hinted at. Just kidding! It’s more than a hint–it’s the twist at the end of the story.

- “The Man in the Rorschach Suit”, wherein a psychologist finds a learned professor purportedly dead on a bus wearing a special shirt. The not-dead research psychologist asks people what they see in his shirt.

- “Henry the Ninth”, wherein climate change (global cooling–remember, this was the end of the world for most of the middle 20th century, child) has driven the population of Great Britain south except for one man who wants to remain.

- “The Lost City of Mars”, wherein a rich man takes an eclectic party on a yacht to search for the Lost City of Mars. They find it, and many are sorry they did.

- “Christus Apollo”, a poem about space travel as the eighth day of creation.

So it has seven science fiction short stories (out of 18 total works), two of which are set on Mars and could have been in The Martian Chronicles but might have been written too late. Include the “weird” stories with a fantastic element, and you get another one or two. The others are contemporary or historical fiction that appeared in mainstream magazines. I have to guess fans of Bradbury’s science fiction would have been disappointed, but perhaps by 1969, they had realized that he was not a science fiction writer by that time but a writer who sometimes wrote science fiction. Personally, I wonder if he punched above his weight in scientific circles based on a couple of early bestsellers (The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451).

He did have all the right opinions, though, compared to Asimov, who escaped the Soviet Union, and Heinlein, who was something else. In “I Sing The Body Electric”, for example, the robot grandmother has a chance to rant about cars being bad and guns being bad. In the early part of this century, gentle reader, we had a term “Sucker punch” for that moment in a book where an author dropped in a little homily about a progressive talking point. Strange, we don’t talk about that a decade or fifteen years later–I guess we presume that is just a feature of contemporary fiction.

There’s also a bit where the grandmother sez (only a page after the anti-automobile sermon):

Tell me how you would like to be: kind, loving, considerate, well-balanced, humane… and let me run ahead on the path to explore those ways to be just that. In the darkness ahead, turn me as a lamp in all directions. I can guide your feet.

This seems an allusion to the biblical (Psalm 119:105, given here in the King James Version which features italics not found in the NIV):

Thy word is a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path.

Coupled with the last poem where technological advance supplants God, and I think we’ve found another who thinks technology (and expertise) will somehow overcome human nature. Which has not proven to be the case.

When I read The Illustrated Man 12 years ago(!), I was similarly unimpressed.

I don’t think I have a lot of Bradbury floating on the to-read shelves, fortunately.

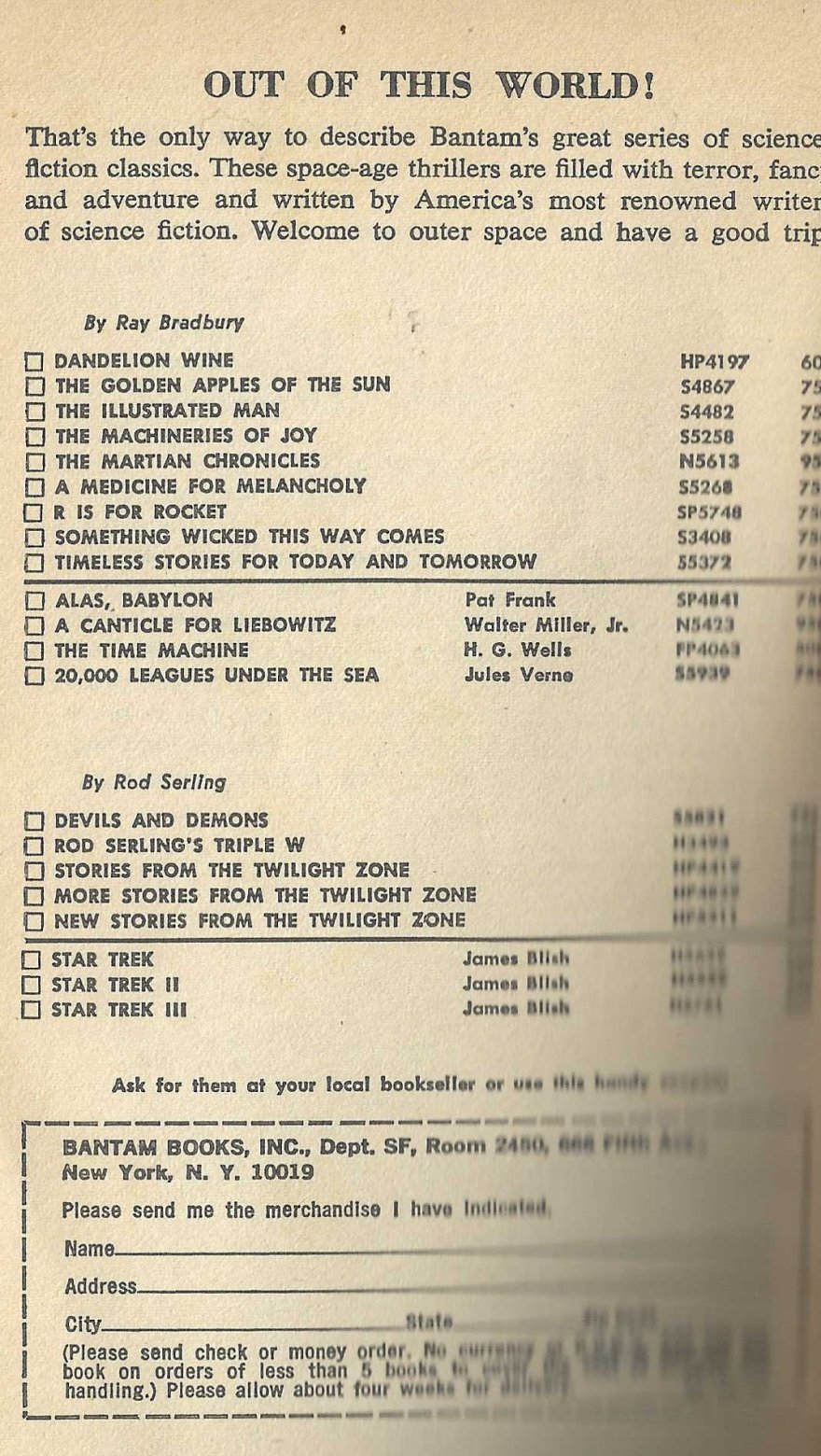

But the list of books also available in the back:

… reminded me I had started working my way through the James Blish Star Trek books earlier this year. I’d probably better hop onto that if I’m going to finish before football season brings monographs and chapbooks and the Christmas season brings the obligatory Christmas novel.

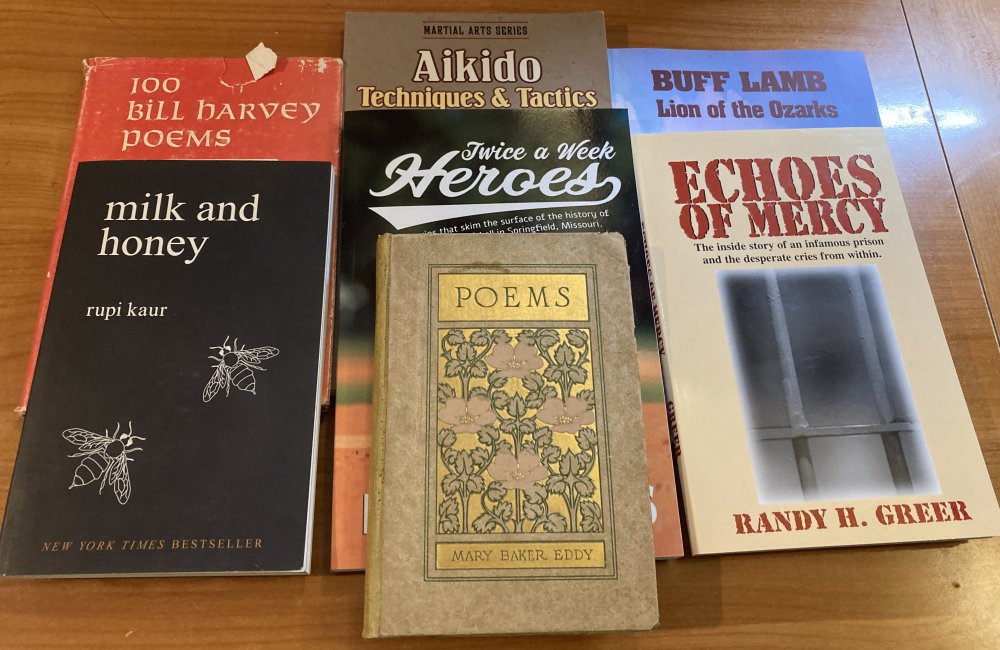

I bought this book

I bought this book  I picked this book up in June

I picked this book up in June

Where the heck did I get this book? A quick search of Good Book Hunting posts does not yield a result. It does not have an ABC Books sticker. It does not have a price penciled on the first page which might indicate another used book store. I certainly did not buy it new as a sixteen-year-old. So I must have picked it up at a garage sale. Perhaps this year’s Lutherans for Life garage sale–I don’t see a Good Book Hunting post for that particular sale this summer, which might mean it was one of a couple books I might have picked up. Without a picture, I have no memory.

Where the heck did I get this book? A quick search of Good Book Hunting posts does not yield a result. It does not have an ABC Books sticker. It does not have a price penciled on the first page which might indicate another used book store. I certainly did not buy it new as a sixteen-year-old. So I must have picked it up at a garage sale. Perhaps this year’s Lutherans for Life garage sale–I don’t see a Good Book Hunting post for that particular sale this summer, which might mean it was one of a couple books I might have picked up. Without a picture, I have no memory. I bought this book for $10

I bought this book for $10  This book completes the four books I bought at

This book completes the four books I bought at  I bought this book

I bought this book

This book bears no copyright date, but some of the poems that are dated come from the late 1960s–and the first is dated 1937 and says it’s the poet’s first poem. So we can assume this is from the 1970s or 1980s–maybe even a little later given that the collection has wingdings between poems that might come from the birth of desktop publishing. Remember, younger readers, desktop publishing referred to being able to lay out your books on your desktop computer for printing, not blogging or e-zines where the work never actually leaves the desktop (which these days includes mobile devices).

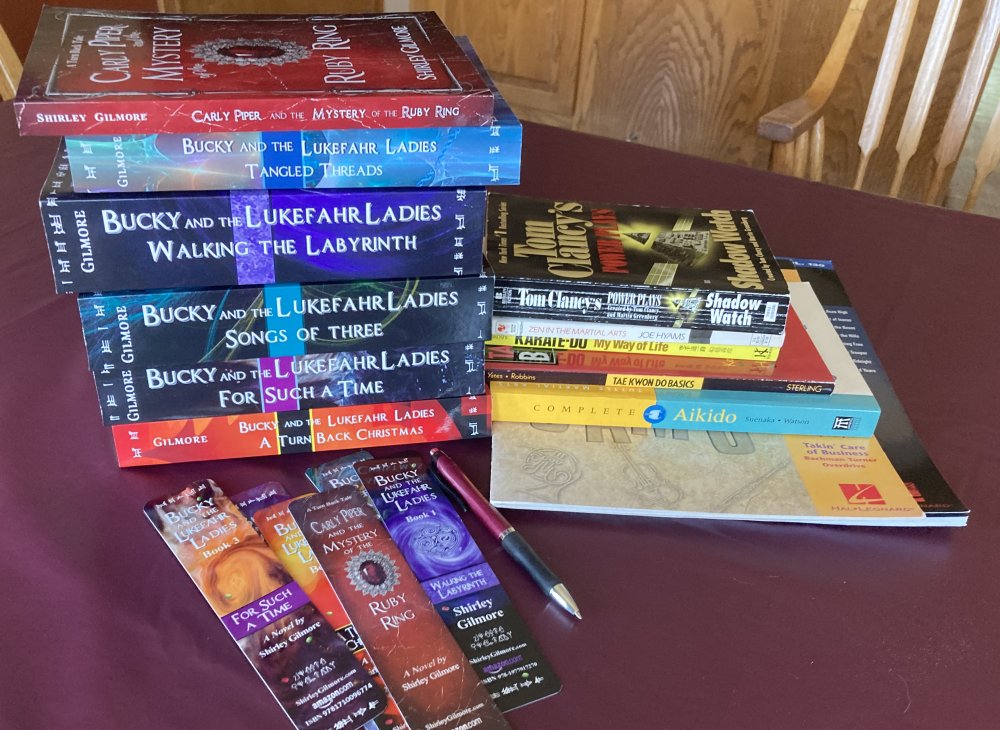

This book bears no copyright date, but some of the poems that are dated come from the late 1960s–and the first is dated 1937 and says it’s the poet’s first poem. So we can assume this is from the 1970s or 1980s–maybe even a little later given that the collection has wingdings between poems that might come from the birth of desktop publishing. Remember, younger readers, desktop publishing referred to being able to lay out your books on your desktop computer for printing, not blogging or e-zines where the work never actually leaves the desktop (which these days includes mobile devices). Well, it’s been a while since I bought this book–I got it at the last LibraryCon,

Well, it’s been a while since I bought this book–I got it at the last LibraryCon,  I bought this book

I bought this book

This book was in the poetry section at ABC Books, but that’s a bit of a misnomer. The author’s bio calls him a social media influencer, and the book reads like a bunch of Instagram posts. Some are a couple paragraphs of prose, and some are “poetry,” although they’re just prose with line breaks.

This book was in the poetry section at ABC Books, but that’s a bit of a misnomer. The author’s bio calls him a social media influencer, and the book reads like a bunch of Instagram posts. Some are a couple paragraphs of prose, and some are “poetry,” although they’re just prose with line breaks. You know, I had almost forgotten that I was working my way through these books earlier this year. So when I was looking at the to-read books in the hallway, I thought, Oh, yeah, and this book provided just what I was looking for: A quick and pleasant read. I mean, I have to get my stats up. I’m only in the 40s in the books read in 2022 list, and it’s almost August. And I’m not sure we’ll have the football package this year for me to browse monographs and chapbooks.

You know, I had almost forgotten that I was working my way through these books earlier this year. So when I was looking at the to-read books in the hallway, I thought, Oh, yeah, and this book provided just what I was looking for: A quick and pleasant read. I mean, I have to get my stats up. I’m only in the 40s in the books read in 2022 list, and it’s almost August. And I’m not sure we’ll have the football package this year for me to browse monographs and chapbooks.

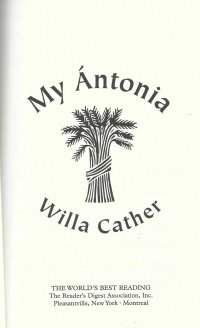

Well, I wish I could say that my confusion between Willa Cather and Eudora Welty is easing with my reading, apparently, a couple of Cather novels in the recent years. Oh, but no. I had this book before me with the author’s name right on it, but I got to thinking Eudora Welty wrote O Pioneers! which I read

Well, I wish I could say that my confusion between Willa Cather and Eudora Welty is easing with my reading, apparently, a couple of Cather novels in the recent years. Oh, but no. I had this book before me with the author’s name right on it, but I got to thinking Eudora Welty wrote O Pioneers! which I read