The 2023 Winter Reading Challenge has a “Wartime Setting” category, and I picked up James Webb’s Fields of Fire as it was the first piece of wartime fiction I laid my hands on, but it looked pretty thick, and my time is running out on hitting all fifteen categories. So when I came across this book, nonfiction and looking shorter, I laid my hands upon it instead. I bought this book in 2009 for just such an occasion. How foresightful I was!

The 2023 Winter Reading Challenge has a “Wartime Setting” category, and I picked up James Webb’s Fields of Fire as it was the first piece of wartime fiction I laid my hands on, but it looked pretty thick, and my time is running out on hitting all fifteen categories. So when I came across this book, nonfiction and looking shorter, I laid my hands upon it instead. I bought this book in 2009 for just such an occasion. How foresightful I was!

In 1967, Charlie Lamb was shot down over North Vietnam and was taken prisoner, and he spent six years as a prisoner of war. This is his account of those years, presented not exactly chronologically, but topically (although with a little bit of chronolgy that evolves). The account does not linger on the torture and deprivation they suffered–it’s pretty matter of fact about it–but it does extol the ingenuity of the men. I mean, at one point, the author, a ham radio operator as a kid, is trying to build a radio out of things he found in a Vietnamese POW camp, including bits of wire and whatnot. He talks about their exercise programs, how they worship in secret, how they exercise, and a bit of how they’re moved around, but by 1973 are stacked in Hanoi as the war turns against North Vietnam.

Thematically, the book is very positive–again, focusing on the ingenuity of the prisoners and not dwelling on the deprivations of their conditions, but for the second book in a row, the book hints at and then deals, more directly, with the author’s divorce. In this case, the author was away for six years and his wife found someone else in the interim. But even then, the author kind of mentions his heartbreak, but even though he does bring a meeting with her for signing the last of the papers, and he tells of how it affected him, his recounting of it still maintains a certain stoicism.

I mean, the title of the book is I’m No Here, but the greater indictment for Generation X–that men such as these were not that much out of the ordinary. Heck, my father, who served during the Vietnam War but was spared, to his everlasting guilt, from serving in Vietnam by the luck of the draw, might have been able to build a radio from spare parts. Can I? No. And my children? Less than I.

So I salute men like Charlie Plumb. Men as we’ve not seen much since.

I did note a couple of things in this book with paper flags, but I won’t give direct quotes, only some comment.

- The ranking officer at the Hanoi Hilton, when he was there, was Captain Stockdale. Admiral Stockdale. Who would be on the Libertarian ticket as the Vice President seven years after this book was written. I have recently saved or printed out an article he wrote based on his rules from his time there.

- He mentions how the Communists pick small, underdeveloped nations to start their trouble in. Well, in the 21st century, the long march is different, ainna?

- He mentions imagining, in the POW camp, a dinner where he’s seated between Marilyn Monroe and Gina Lollobrigida. As we on the Internet know, Gina Lollobrigida passed away on January 16 of this year, which was a loss to men of a certain age, and unfortunately, a discovery and loss to men of another certain younger age.

Also, the book has a bit of a triumphalist tone. Because in 1973, Saigon had not fallen, and we would not see the helicopters lifting off from the rooftops of Saigon in what has been a recurring theme in American wars since then. One wonders (no, one knows) if the decline of competence in men (and women) led to the decline of the nation’s fortunes. Perhaps the G.I. Bill was not all that.

It’s been a while since I listened to most or perhaps all of this course. My beautiful wife discovered that the DVD player in our old, but newish to us, truck would “play” DVDs, but when it played them, it would not display the video on the new-then-fangled touchscreen video control. Instead, it would play the audio. Which opened us up to “listening” to DVD courses while driving. Except that the track listing was not as straight-forward as actual CDs. The track listing includes menus you cannot see, titles and whatnot, and other things. So I listened to this course in May and June, culminating in our trip to Wisconsin. But somewhere on the trip, we reached a point where we were retreading the same ground, hearing the same course again, so either we got the discs out of order or mangled returning to our place on the last lecture or three. So we removed it from the car’s audio system and went onto the next course. And then we didn’t drive anywhere of consequence. Given that my oldest son is old enough to drive he and his brother to school, and the round trip in the car is no longer an hour and a half per day, who knows when I will finish another course?

It’s been a while since I listened to most or perhaps all of this course. My beautiful wife discovered that the DVD player in our old, but newish to us, truck would “play” DVDs, but when it played them, it would not display the video on the new-then-fangled touchscreen video control. Instead, it would play the audio. Which opened us up to “listening” to DVD courses while driving. Except that the track listing was not as straight-forward as actual CDs. The track listing includes menus you cannot see, titles and whatnot, and other things. So I listened to this course in May and June, culminating in our trip to Wisconsin. But somewhere on the trip, we reached a point where we were retreading the same ground, hearing the same course again, so either we got the discs out of order or mangled returning to our place on the last lecture or three. So we removed it from the car’s audio system and went onto the next course. And then we didn’t drive anywhere of consequence. Given that my oldest son is old enough to drive he and his brother to school, and the round trip in the car is no longer an hour and a half per day, who knows when I will finish another course? The

The  The

The  The

The

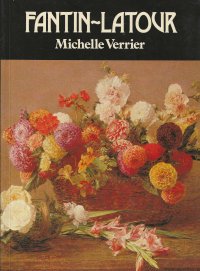

This book sat on my sofa-side table, an old Sauder printer stand actually–past the half century mark, and I still have two Sauder printer stands from the middle 1990s as household furniture–for over a year. Although in past years, I have browsed poetry or art monographs during football games, I did not do so this year. I’m not sure whether it’s that my attention span has withered or that I cannot switch between football plays and text as easily as I could when I was a younger man or if my current selection of monographs and poetry chapbooks does not compel me to read them. Maybe both.

This book sat on my sofa-side table, an old Sauder printer stand actually–past the half century mark, and I still have two Sauder printer stands from the middle 1990s as household furniture–for over a year. Although in past years, I have browsed poetry or art monographs during football games, I did not do so this year. I’m not sure whether it’s that my attention span has withered or that I cannot switch between football plays and text as easily as I could when I was a younger man or if my current selection of monographs and poetry chapbooks does not compel me to read them. Maybe both.

The

The  The

The  The

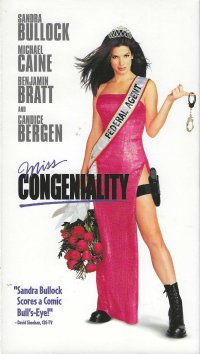

The  Wow, this film is twenty years old, which makes it an old movie by now. Which means it’s about time for me to watch it. I mean, it’s not like a black and white film, which it might well have been if it had been a movie twenty years old when I was born. But its humor is that of another time, when you could make fun of stereotypes and whatnot.

Wow, this film is twenty years old, which makes it an old movie by now. Which means it’s about time for me to watch it. I mean, it’s not like a black and white film, which it might well have been if it had been a movie twenty years old when I was born. But its humor is that of another time, when you could make fun of stereotypes and whatnot.