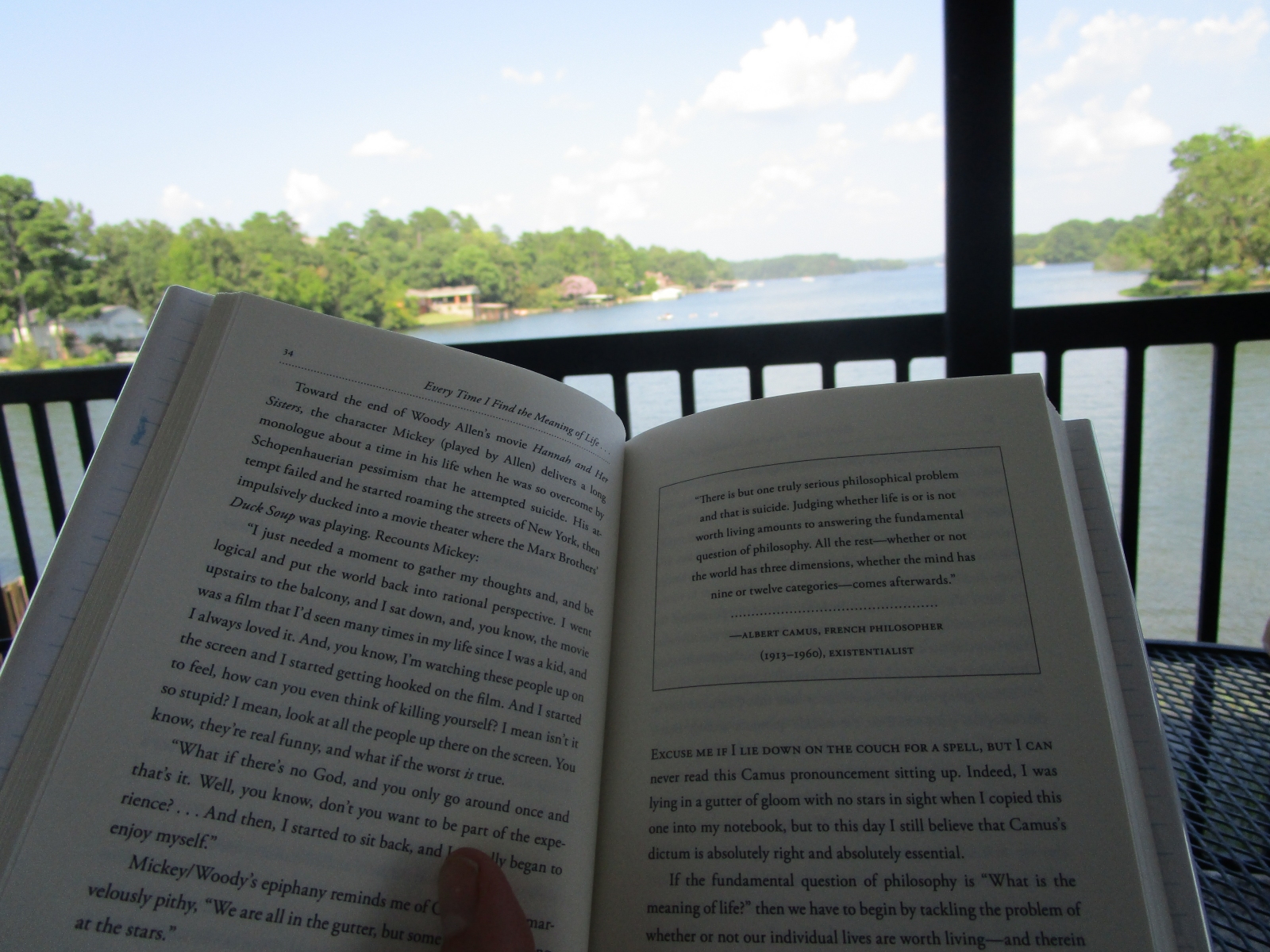

I started reading this book a couple years back (sometime after Meditations by Marcus Aurelius), but my drive through it petered out as it, like the earlier work, is thematically repetitive. However, this time I figured I’d slog it out, as I’ve learned some patience and some discipline in reading longer works. So I did over the course of many months.

I started reading this book a couple years back (sometime after Meditations by Marcus Aurelius), but my drive through it petered out as it, like the earlier work, is thematically repetitive. However, this time I figured I’d slog it out, as I’ve learned some patience and some discipline in reading longer works. So I did over the course of many months.

The book was not written by Epictetus; instead, it was written down by one of his students and is based upon that student’s notes on Epictetus’s classes, essentially, in Stoic philosophy. This accounts for some of the repetitive nature of it and why the book is not developed as a treatise; rather, Epictetus revisits certain themes several times. One can imagine him telling the same lectures to a different group of students. At one point, he even tells the transcriber to stop writing this stuff down. Which the transcriber does not.

At any rate, I took some positive things from the book. One of the greatest Stoic themes in the book is, to Americanize it, that a man has got to know his limitations. That which you can control is not so much events, not other people, not the world around you, but your own will. You can’t even really control your own body, not completely. So don’t search for happiness in these things but only in the way you deal with things and how you live in spite of them. Okay, that’s good stuff and a valuable lesson there.

However, Epictetus extends this principle to not ascribing value to other things I consider important.

Nay, these arguments of all others make those who adopt them obedient to the laws. Law is not what any fool can do. Yet see how these arguments make us behave rightly even towards our critics, since they teach us to claim nothing against them, in which they can surpass us. They teach us to give way in regard to our poor body, to give way in regard to property, children, parents, brothers, to give up everything, resign everything: only our judgements they reserve, and these Zeus willed should be each man’s special property. How can you call this lawlessness, how can you call it stupidity? I give way to you in that wherein you are better and stronger than I: where, on the other hand, I am the better man, it is for you to give way to me, for I have made this my concern, and you have not. You make it your concern, how to live in a palace, how slaves and freedmen are to serve you, how you are to wear conspicuous raiment, how you are to have a multitude of huntsmen, minstrels, players. Do I lay claim to any of these? But you, for your part, have you concerned yourself with judgements? Have you concerned yourself with your own rational self? Do you know what are its constituents, what is its principle of union, how it is articulated, what are its faculties and of what nature? Why are you vexed then, if another who has made these things his study has the advantage of you here?

Epictetus points out that your family and your children are not your volition, so they’re not really ultimately valuable. Only your will is. In many places and in many different ways, Epictetus pledges a certain servility to the Tyrant and to nature and acceptance of whatever they decide for you. It’s like the first part of the Serenity Prayer (“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,”) without the rest (“The courage to change the things I can,/And the wisdom to know the difference.”).

The book does allude to the right way to live, seeking to live according to God’s will, but it’s rather light on what that will is or what universal precepts might dictate proper action (live according to reason and within your limitations are nebulous at best).

Still, I’m glad I read it. I’ve got some additional classic literature cred, which impresses pretty much nobody I know, and it does give me some ideas and perspective to put into practice in my life. As I explained to my beautiful wife, philosophy is just self-help books with bigger words in them.

Books mentioned in this review: