Ah, gentle reader. I am certainly playing fast and loose with the 2024 Winter Reading Challenge. Although I did not use The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam or The Broken Spear as the Author of Different Race/Religion Than Your Own book because those books were collected/compiled/edited by presumable Christians and people of European descent, I did enter Tales from the Missouri Tigers in the School Setting category even though it’s more a sports book than a school book (but university sports). And now, gentle reader, I have fallen even lower.

Ah, gentle reader. I am certainly playing fast and loose with the 2024 Winter Reading Challenge. Although I did not use The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam or The Broken Spear as the Author of Different Race/Religion Than Your Own book because those books were collected/compiled/edited by presumable Christians and people of European descent, I did enter Tales from the Missouri Tigers in the School Setting category even though it’s more a sports book than a school book (but university sports). And now, gentle reader, I have fallen even lower.

The Winter Reading Challenge has a Neurodivergent character. Heaven help me, but I was not going to wade back into The Sound and the Fury again for a mug. And I’ve already read Of Mice and Men recently (what? twenty years ago recently?). I remembered that I had a copy of this novel in the Reader’s Digest Select Editions format. I “ordered” this and, apparently, four other such editions back around the turn of the century (the volume containing this book is from 2004). Reader’s Digest (not italicized as it’s the company, not the periodical) would send out a teaser for offering a free book for your review, and then you can cancel or get any one such book every month or two on subscription unless you canceled. I was pretty good at canceling, and I accepted the free offer a number of times (but did “buy” a book or two). These Select Editions are paperbacks, unlike Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, so I thought they were the complete text. But as I started The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, I noticed it was under 200 pages, and not even Mack Bolan books of the era fell under that. With some trepidation, I turned to the front of the book (this novel is fourth of four in the volume), and…. Selected and Edited. Oh. This is a Reader’s Digest Condensed book in a cheaper package for people who, at the turn of the century, might have thought that the Condensed Books were for old people (as an aside, I hardly ever see Condensed Books at garage sales, estate sales, or book sales any more–have they all been pulped by now?). But I am going to count it as a complete novel because I really, really don’t want to wade into the children’s section of the library, where one can easily find entries for every category on the Winter Reading Challenge list.

At any rate, I remembered that this book focused on a neurodivergent child, and so it does. The first person, fifteen-year-old Christopher, is autistic. The book starts when Christopher is out walking late at night, which he likes to do because it’s quiet, he finds the neighbor’s poodle dead on a lawn, stabbed with a garden fork. Police initially think that he did it, but he did not, so he starts to investigate and to write this book to describe his investigation.

Christopher tells us about his life a bit, slowly working in details about his special school and life with his father, an HVAC man who has been raising Christopher since his mother died of a heart attack. Christopher steps outside of his comfort zone to talk with the neighbors in his investigation, including an old woman who tries to befriend him. Christopher’s father orders him to stop investigating and bothering people and takes away Christopher’s manuscript of the book. While looking for the book, Christopher finds a stack of letters from his mother. She did not die, as his father said, but instead could no longer take the pressure and/or responsibility of raising Christopher and ran away with a married neighbor. Christopher’s father discovers him with the letters and explains that not only did his wife run off with another man, but he had hoped to become a couple with the left-behind wife, and when he had a falling out with her, he killed the ill-tempered dog. This sets Christopher off, and he must really leave his comfort zone and travel to London to be with his mother. Who is falling out of love with the man she ran off with. The book ends kind of media en res as well; Christopher returns to Swindon to take his Maths exams; his parents can be in the same room together; and Christopher’s father tries to make amends with Chistopher.

It’s a thin plot, and the whole purpose of the book is to imagine and experience the imagined voice of an autistic teenager. Which it does with some limited success, I suppose, but I imagine that it’s different enough that a lot is lost or transmogrified. A couple of times the narrator says that he does not imagine things, but he goes off on flights of fancy a time or two. The narrator also describes clinically how he perceives things instead of simply perceiving them that way. Although I suppose that it would be too jarring to try to completely reproduce it.

The book was originally sold both as an adult novel and a YA novel with different packaging and covers for each. It does kind of have more of an young adult book to it, but part of that might be in the Reader’s Digest trimming.

You know, I read this fairly quickly and probably got a good flavor for it. Perhaps I should give these Selected Editions and Condensed Books (where I can find them) a second look. I am not especially a fan of modern and mainstream novels, but reading these would give me a deeper overview of the works than the Wikipedia entries. And I could count them as a complete book in my annual tabulation (and the Reading Challenge categories). So maybe I should add them to the list of things I hope to read this year after the Reading Challenge. Along with the rest of the Sharpe’s books I own, one or more volumes of The Story of Civilization, and pretty much whatever catches my eye in the interim.

Well, gentle reader. Well, well, well. For starters, I watched this film last month and it has lingered on my desk that long. To be honest, I’ve been fairly busy with the

Well, gentle reader. Well, well, well. For starters, I watched this film last month and it has lingered on my desk that long. To be honest, I’ve been fairly busy with the  Ah, gentle reader. I was going to lead off by saying “I’ve already read this book,” but

Ah, gentle reader. I was going to lead off by saying “I’ve already read this book,” but  Ah, gentle reader. I am certainly playing fast and loose with the

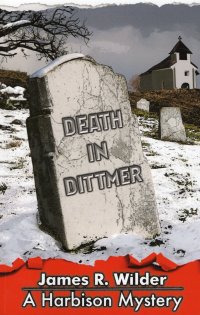

Ah, gentle reader. I am certainly playing fast and loose with the  Well, gentle reader, when I bought this book

Well, gentle reader, when I bought this book  Ah, gentle reader, of course I did not have to rely on

Ah, gentle reader, of course I did not have to rely on  I picked up this book

I picked up this book  The

The  I said when I bought this book

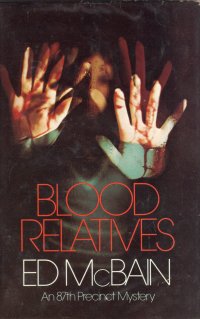

I said when I bought this book  You are not mistaken, gentle reader; I have written a book report on this 87th Precinct novel before (in

You are not mistaken, gentle reader; I have written a book report on this 87th Precinct novel before (in  I bought this book in

I bought this book in

This, of course, was the first book I read for the

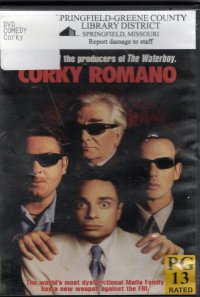

This, of course, was the first book I read for the  Ah, gentle reader. I took my beautiful wife to see this film in the theater. We were young, and we went to the movies often, apparently, and I not only made her suffer through not only films based on Saturday Night Live sketches, but also films starring Saturday Night Live alum. For some reason, we thought this would be a funny film, but she was not impressed.

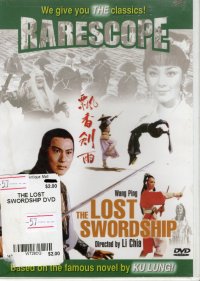

Ah, gentle reader. I took my beautiful wife to see this film in the theater. We were young, and we went to the movies often, apparently, and I not only made her suffer through not only films based on Saturday Night Live sketches, but also films starring Saturday Night Live alum. For some reason, we thought this would be a funny film, but she was not impressed. Ah, gentle reader, I picked up this film with a heavy heart. As I mentioned

Ah, gentle reader, I picked up this film with a heavy heart. As I mentioned