It took me two tries to read this book; I started it last year and got about halfway through it, enjoying it for what it was before taking it out of my pocket as my carry book and planning to read the last half of it all at once. That didn’t happen, so I started it again this year as my carry book and keeping it in pocket until I finished it.

It took me two tries to read this book; I started it last year and got about halfway through it, enjoying it for what it was before taking it out of my pocket as my carry book and planning to read the last half of it all at once. That didn’t happen, so I started it again this year as my carry book and keeping it in pocket until I finished it.

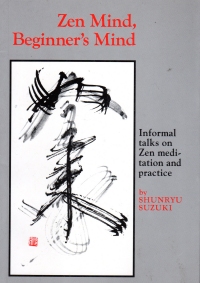

The book is a collection of informal talks given by the author after sitting with students practicing zazen. The author founded the first Zen temple in the United States, and this book collects some of his insights into Zen.

So, to talk about Buddhism, I find it easy to break it into three parts, and perhaps this is something we could do with all religions. These parts include:

- The cosmological/theological/heavy philosophy (the eternal, the afterlife, interpretation of the texts).

- Practical philosophy (the guidance to everyday living).

- The practice (the things to do when you’re a part of the religion).

Although this book does lightly touch upon the first (that the individual is akin to a droplet of a stream in a waterfall–part of the stream, then alone briefly, and then part of the stream; that breaking out of the cycle of karma is the goal of Zen, as karma is a self-centered way of thinking), it focuses mostly on the last two, which is fitting: the talks were give after the practicing with an eye toward improving that. Basically, it’s to sit still, in the proper posture, breathe right, and clear your mind. Okay, there’s a bit more to it than that, such as dealing with distractions within and without, but that’s it. Strangely enough, although they’re from different schools, this book and Start Here Now don’t differ much on the practice of Buddhist meditation. Perhaps the difference between Shambhala and Zen schools lie at the higher levels of philosophy.

I was most interested in the middle point above; Practical philosophy. Buddhism focuses on recognizing the transience of this life and all of its moods, emotions, and events. Buddhism is much akin to Stoicism, so much that I checked to see if the sutras might have made their way back to Rome before Zeno (the other Zeno) founded the Stoic school. It was only about a hundred years, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the sutras might have made their ways west before the later thinkers made their marks. Both philosophies urge that calmness and detachment which, if you know me, you probably can tell I appreciate.

The Buddhists also talk about nothingness, but when they do not mean it like the Existentialists do. In the Buddhist sense, “nothing” is the eternal something from which everything is drawn. In the Existentialist sense, “nothing” is the opposite of that.

The book is written in the proper Buddhist style, wherein the koanesque nature might make you go “Huh?” The question of the sound of one hand clapping appears. Once you get it into your head that the Buddhist way is to see the gestalt and the particular at the same time, you can understand it better (the forest is the trees; the tree is the forest). Some of them do go into paradox territory, but as with any religion, eventually you have to make your peace and accept some paradox.

So I enjoyed the book and got some insights into detachment (and a couple of posts quoting the book–search for the wisdom of shunryu suzuki). But it’s a practical and practice primer on Buddhism, akin to the Max Lucado Christian books: A bit of how to live as a Buddhist, but without the implications and intimations of the religion that you get from the heavier books by Kierkegaard, Niebuhr, Tillich, and so on. If you believe Alex G. Smith, that’s how the Buddhists hook you, with their practical philosophy and practice, but that’s how the Christians hook you, too (Tolstoy’s favored religion features that sort of peasant, practical religion, and that explains why he equates religions based on this practical philosophy level.

Now, where was I before I started name-dropping other things I’ve read? Oh, yes: The book is a good primer into Zen Buddhist thought, especially the practical philsophy and practice components, and you could learn something from it. But don’t read it and declare yourself a Buddhist, as it really lacks a cosmological component that explains it all. Of course, the Zen would argue that you don’t need to know it, just to do Zen. But I’m a Western kid, and I expect a bit more in a complete belief system. Which is why I’ll never be a Buddhist.