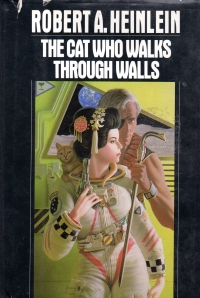

This book started out pretty good. Well, I mean, it is one of Heinlein’s adult books, so it’s very talky, with action broken up by a lot of banter and philosophizing. It starts out with a bang: A former military officer, hiding out from something in his past as a writer on a space station, has someone invoke that Dreaded Secret to get his attention at a night club. Before the man can explain what he wants beyond that the main character must kill a fellow space station resident before noon tomorrow or they’ll all perish, the man demanding the hit is killed and the hit is covered up very neatly by the restaurant staff. Then, the owners of the space station are in some hurry to push the man out or off the station, so he decamps to the moon and a series of cities on the moon just one step ahead of disaster, attempts on his life, or bandits.

This book started out pretty good. Well, I mean, it is one of Heinlein’s adult books, so it’s very talky, with action broken up by a lot of banter and philosophizing. It starts out with a bang: A former military officer, hiding out from something in his past as a writer on a space station, has someone invoke that Dreaded Secret to get his attention at a night club. Before the man can explain what he wants beyond that the main character must kill a fellow space station resident before noon tomorrow or they’ll all perish, the man demanding the hit is killed and the hit is covered up very neatly by the restaurant staff. Then, the owners of the space station are in some hurry to push the man out or off the station, so he decamps to the moon and a series of cities on the moon just one step ahead of disaster, attempts on his life, or bandits.

Then, about 250 pages into the book, he finds his new bride (the one with him at the nightclub and with whom he banters a bunch) recruits him into Time Corps, and I thought, Here’s where the real book begins.

But it did not.

I guess I confused Heinlein with a thriller writer who amps it up and then ties it all together neatly.

Because after a hair’s-breadth escape on the moon from dark forces, he finds himself recuperating on Lazarus Long’s polyamory paradise from Time Enough For Love, and many of those characters make appearances, and then the Time Corps has to do something for some reason, and there’s a tribunal with gunslinging, and he undertakes the mission. The secret of his past? Glossed over. The stuff from the beginning of the book? The work of other forces. Are those other forces dealt with? The end.

Man, I have to stick with the old Heinlein stuff like Rocket Ship Galileo or even The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag. Or, I suppose, Job (when I get to it, John–which reading this has probably forestalled a bit).

I dunno. Maybe I’m just in a place these days where science fiction ultimately disappoints me or something.

Books mentioned in this review:

Like almost anything RAH wrote after “Stranger” (other than “Friday” and his critique of Niven and Pournelle’s “Mote in God’s Eye”) “Cat” suffers from the author’s unwillingness (or maybe inability) to do what he had done so well up to that point: Tell a good yarn. The talky passages are one symptom, and his whole “world as myth” conceit that he used with Lazarus Long and the “Number of the Beast” ideas are another. And his bizarre ideas about sex rarely help him, as whatever narrative he’s put together grinds to a squickening halt after someone bops his own mom or something for no other reason than Heinlein wanted it in there. “Job” has more narrative strength than “Cat” or the gross “To Sail Beyond the Sunset,” but its final act falls apart when the story goes cosmic.

That’s definitely the sense I get from them. Also, I’m not sure what to make of the titular cat in this particular tale. He just sort of walks through walls at times and doesn’t add much. Perhaps its significance is too deep for me along some axis.