Gentle reader, I have been reading, although not as much as normal over the end of the summer, and I have been really slow at writing up my thoughts on the books I have (I have read three and almost five in the last month). I finished this book on September 13, and I am only now getting around to typing up my thoughts which are likely to be even more brief than my normal book reports as I have probably forgotten what I want to say.

Gentle reader, I have been reading, although not as much as normal over the end of the summer, and I have been really slow at writing up my thoughts on the books I have (I have read three and almost five in the last month). I finished this book on September 13, and I am only now getting around to typing up my thoughts which are likely to be even more brief than my normal book reports as I have probably forgotten what I want to say.

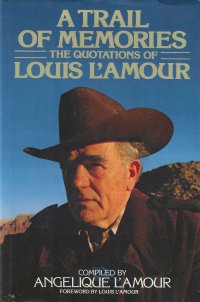

As I mentioned when I reviewed A Trail of Memories: The Quotations of Louis L’Amour, I said this looked, based on the quotations in the aforementioned compilation, that the L’Amour book I would like to read first. And as I picked it up in Kansas Labor Day weekend, I dived right into it.

A brief synopsis: Bendigo Shafter and his brother are working on a wagon train on the Oregon trail, but the they decide they will not make it through the mountains before the winter seals the passes, so they build a town in Wyoming. Some unsavory characters appear, Shafter saves an Indian’s life and the Indian vows revenge, a known gunman protecting two children wides up one winter night, and various other things happen, challenging the good men of the town. One local man finds a little bit of gold, which makes him the target of some bad men. Shafter is chosen to take a pool of the townsfolk’s money to Oregon to buy cattle for them, a trip that takes him almost a year. He starts alone but befriends a couple of Indians on the way, and they join the town. When Shafter returns, he finds some of the bad men have basically gotten themselves put into positions of authority until Shafter and his brother intervene. Then Shafter finds some gold, goes back east to New York City looking for the now-grown little girl he earlier saved, and when he returns to Wyoming he goes with the aged Indian he met on his cattle drive to an ancient Indian monument of some sort.

It’s basically a coming of age story telling about how Bendigo grew to be a man, which give L’Amour time to pontificate on manliness in spots. They’re akin to the little asides that Pendleton put into his Executioner novels, a bit of philosophizing to add depth, although L’Amour does more of it. And although Friar said the last third of it was a bit weak–I’m not sure whether that’s after the cattle drive or not–I did not find much of it dramatic. I mean, in the tense scenes and trials, Bendigo pretty much knows what to do and does it, so I didn’t feel like he was ever in any danger. I don’t know–your mileage may vary. I have several other L’Amour books on my to-read shelves to review, and I will learn if that’s just the way he wrote.

I cannot help but compare the arc a bit to My Ántonia in that the main character, the young man who gets educated, goes back east and compares it to his experience in the west. Unlike that book, though, Bendigo Shafter ultimately prefers the west. Which is because this is a Western and not literary fiction.

At any rate, I flagged a couple things ago a month ago. Let’s see if I remember why.

Bendigo is better read than I am.

Fixing myself a cup of coffee, I then went up the ladder to my bed and got the book I was reading. Only this time she had given me two at the same time, and I decided to take both of them down. The first was the Essays of Montaigne. The second was the Travels of William Bartram.

As you might recall, gentle reader, I started the Montaigne five years ago and only made it a couple of essays in, after which it remained on my dresser for a year or two before I put it back into the stacks. Which is not the longest a book has been unread on a book accumulation point. I’ve not made it through the Classics Club collection on Plato nor the first volume of Copleson’s History of Philosophy in far longer periods of time.

I Have Been To The House

When they had gone old Uruwishi came out of the brush with his old Hawken rifle.

The Hawken House, where the maker of the Hawken rifle lived, is in Old Trees, Missouri, and is home of the Historical Society. I actually have the commemorative tile from being a member prominently displayed on my desk.

Everybody Goes To Delmonico’s.

On his New York trip, Shafter does.

We met at Delmonico’s. It was, at the time, the most favored eating place in the city.

Come to think of it, this book takes place at the same time as Clarence Day’s Life with Father sketches. They went to Delmonico’s, too.

Mindfulness in the 19th Century As Told In The 1970s.

It is my great gift to live with awareness. I do now know to what I owe this gift, nor do I seek an answer. I am content that it be so. Few of us ever live in the present, we are forever anticipating what is to come or remembering what has gone, and this I do also. Yet it is my good fortune to feel, to see, to hear, to be aware.

Buddhism was making some inroads in the 1970s. I wonder if this influenced L’Amour.

So it was an interesting read, and I will not avoid the other L’Amour books when I’m going to the bookshelves for something to read.

And I cannot help but note that I have metamorphosed into a man who reads Louis L’Amour books. What kind of man is that? Oh, yeah, an old man.

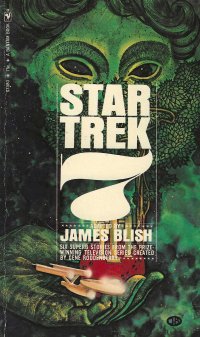

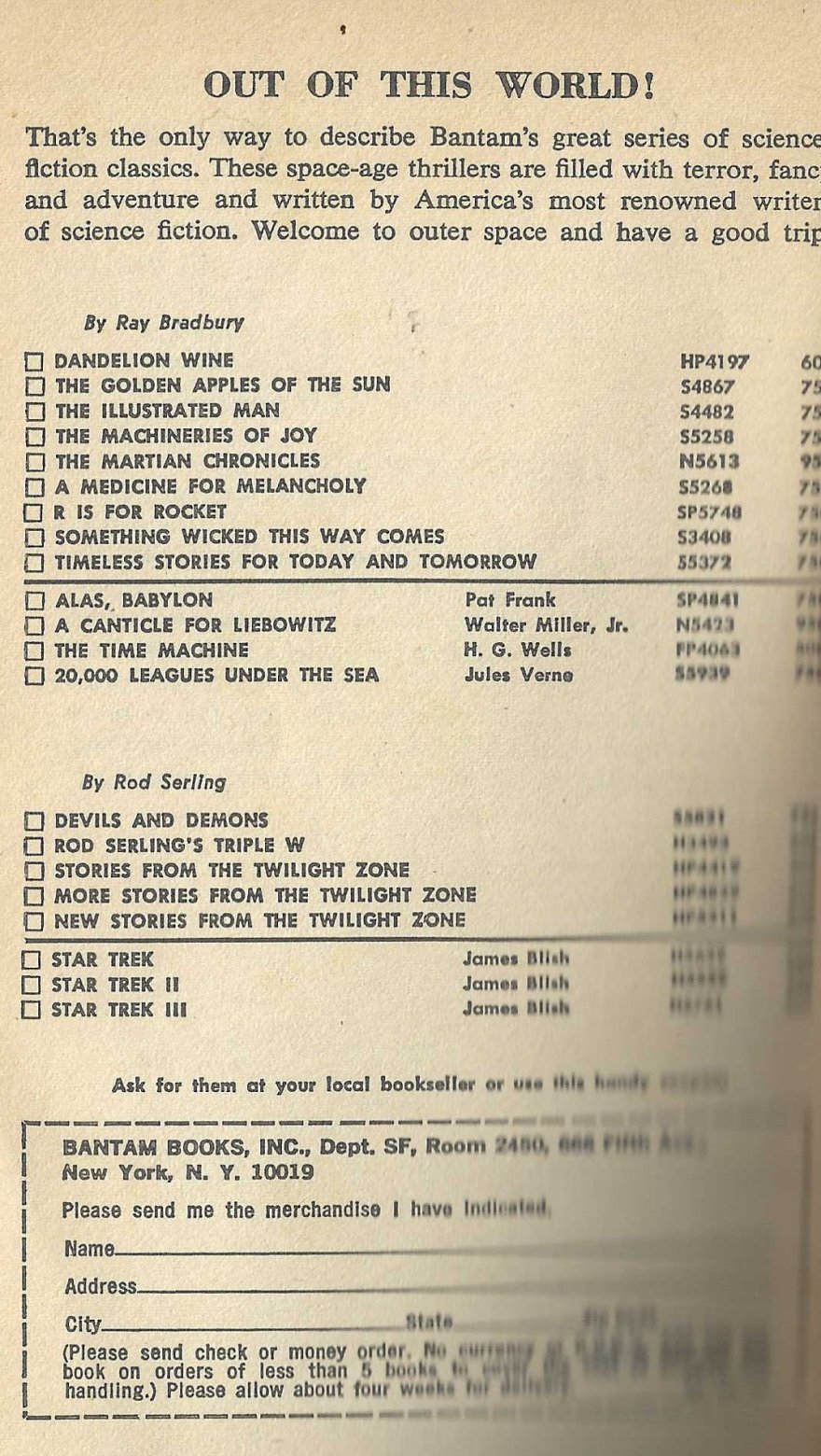

Well, make this my year of completing sets, or at least groups of books that I have. I mean, I finished all of the books in the Executioner series that I own; I finished the set of James Blish Star Trek books I had on my to-read shelves; I finished the Doubleday children’s books I’d picked up, perhaps for my children but never shared with them. Since I only had three books in the six-book Ashton Ford series, why not?

Well, make this my year of completing sets, or at least groups of books that I have. I mean, I finished all of the books in the Executioner series that I own; I finished the set of James Blish Star Trek books I had on my to-read shelves; I finished the Doubleday children’s books I’d picked up, perhaps for my children but never shared with them. Since I only had three books in the six-book Ashton Ford series, why not?

As I mentioned, gentle reader, we have

As I mentioned, gentle reader, we have  Well, I seasoned this book well enough. I bought it

Well, I seasoned this book well enough. I bought it  I got this book at ABC Books during a book signing

I got this book at ABC Books during a book signing  This might have been only the second Saint book (or is it The Saint book?) that I’ve ever read. The first would have been a modern paperback (well, then modern) that I read in high school or thereabouts. It was one passed onto us by my Aunt Dee right about the time we moved into the house down the gravel road. We got a small stack of books from her–less than I would buy if I went hog wild at a church or friends of the library book sale–but my aunt introduced me to Ed McBain, Anne Rice (Interview with the Vampire, which is the only Anne Rice I’ve actually read), and, perhaps The Saint. So it’s been a while.

This might have been only the second Saint book (or is it The Saint book?) that I’ve ever read. The first would have been a modern paperback (well, then modern) that I read in high school or thereabouts. It was one passed onto us by my Aunt Dee right about the time we moved into the house down the gravel road. We got a small stack of books from her–less than I would buy if I went hog wild at a church or friends of the library book sale–but my aunt introduced me to Ed McBain, Anne Rice (Interview with the Vampire, which is the only Anne Rice I’ve actually read), and, perhaps The Saint. So it’s been a while. Well, having just finished the Doubleday children’s books I own with

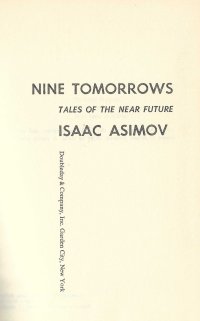

Well, having just finished the Doubleday children’s books I own with  Wow, has it been five years already since I read

Wow, has it been five years already since I read  You know, I did not have this particular volume of the series before I picked this one up, unlike so many of the others for whom I wrote book reports in 2005. So I don’t have to add appendixes to the filenames for the image or the book report text file on my desktop. Which I did anyway out of habit.

You know, I did not have this particular volume of the series before I picked this one up, unlike so many of the others for whom I wrote book reports in 2005. So I don’t have to add appendixes to the filenames for the image or the book report text file on my desktop. Which I did anyway out of habit. It’s been four years since I read the first book in Don Pendleton’s Ashton Ford series,

It’s been four years since I read the first book in Don Pendleton’s Ashton Ford series,  Gentle reader, I have been reading, although not as much as normal over the end of the summer, and I have been really slow at writing up my thoughts on the books I have (I have read three and almost five in the last month). I finished this book on September 13, and I am only now getting around to typing up my thoughts which are likely to be even more brief than my normal book reports as I have probably forgotten what I want to say.

Gentle reader, I have been reading, although not as much as normal over the end of the summer, and I have been really slow at writing up my thoughts on the books I have (I have read three and almost five in the last month). I finished this book on September 13, and I am only now getting around to typing up my thoughts which are likely to be even more brief than my normal book reports as I have probably forgotten what I want to say. Well, gentle reader, I asked in my

Well, gentle reader, I asked in my  So, apparently, as I worked my way through this set of books eighteen years ago, my book report for

So, apparently, as I worked my way through this set of books eighteen years ago, my book report for  I actually started reading this before I started

I actually started reading this before I started

I bought this book

I bought this book  I picked this book up in June

I picked this book up in June  Where the heck did I get this book? A quick search of Good Book Hunting posts does not yield a result. It does not have an ABC Books sticker. It does not have a price penciled on the first page which might indicate another used book store. I certainly did not buy it new as a sixteen-year-old. So I must have picked it up at a garage sale. Perhaps this year’s Lutherans for Life garage sale–I don’t see a Good Book Hunting post for that particular sale this summer, which might mean it was one of a couple books I might have picked up. Without a picture, I have no memory.

Where the heck did I get this book? A quick search of Good Book Hunting posts does not yield a result. It does not have an ABC Books sticker. It does not have a price penciled on the first page which might indicate another used book store. I certainly did not buy it new as a sixteen-year-old. So I must have picked it up at a garage sale. Perhaps this year’s Lutherans for Life garage sale–I don’t see a Good Book Hunting post for that particular sale this summer, which might mean it was one of a couple books I might have picked up. Without a picture, I have no memory. I bought this book for $10

I bought this book for $10  This book completes the four books I bought at

This book completes the four books I bought at  I bought this book

I bought this book