You could probably have guessed after I bought a couple books while out of town for the night that I’d pick up the shortest book to read in my hotel. And you would be right.

You could probably have guessed after I bought a couple books while out of town for the night that I’d pick up the shortest book to read in my hotel. And you would be right.

As I mentioned, I saw this play in college. Ah, my senior year: I saw a large number of plays with a number of comely young ladies, none of whom was interested in me. Well, maybe a couple were and I was oblivious to it. I had to attend this play for one of my classes, and I sat next to a young lady who I knew from the writer’s club. After the play, we walked out together, and she straightened my tie. Did that indicate interest? I don’t know. When reading others’ emotions and acting upon them, I’m a chimp at the space shuttle controls: I know something’s happening, and I know I should do something, but I just press the wrong buttons.

At any rate, I remember the play not only because of the young lady but also because the play disturbed me a bit. It’s told from the point of view of an English student reminiscing about his family life and his parents’ marriage which ends while he’s at school. I, of course, had studied a bit of Thomas Hardy at the time (one of the devices of the play is that the narrator talks about analyzing Hardy’s works as he’s analyzing his parents and perhaps their influence upon him). As the child of a broken home (relatively fresh at that, what, with their marriage still longer than the period they’d been divorced), I felt for the kid. Who was older than I was at the time.

So I saw the book, and I remembered almost viscerally the reaction I had to the play at the time, so I bought it and read it again. As an adult (older than my parents when they divorced and almost as old as my father was when he died), I don’t get quite the poignancy that I did then when I identified with the lad, but I do still have a bit of sadness for the characters in the play. I think it’s billed as a comedy, but it’s more a tragedy than a comedy. Even though the moments from the play stuck with me–I’d forgotten a part where a priest imitates bacon, but when I got to it in the book, I immediately remembered the scene on stage.

So it’s a good play, all right.

The edition I have has a lot of end notes from the playwright (who played the main character in the big New York production of it in the middle 1980s) giving a lot of direction for the direction of the play, including some interpretations that he did not care for in some productions. I’ll be honest, that’s a bit of cheating: In my playwrighting class, the professor said to put all that in the words and stage directions, and to put only the bare minimum in to allow for as much interpretation as you can stand. So the end piece seems a little uncricket.

Also, this book is again a book club edition. Which means our parents or grandparents liked plays enough to buy them from a book club. I cannot even imagine that. There aren’t that many people who buy plays these days (or maybe it’s just me), but I don’t remember seeing many of them in the book stores or book sales I frequent–I know, as I buy them. That’s a shame, as they’re often nice, quick reads with impact beyond their word count.

As you might remember, I bought this book

As you might remember, I bought this book  I got this book at a later time than the Korea guide books (

I got this book at a later time than the Korea guide books ( I started this book, and I thought, “This is better than some of the Executioner books, surely.” The writing is a little thicker, a little richer than you get in the least of the Mack Bolan books. However, there was some foreshadowing that all was not right.

I started this book, and I thought, “This is better than some of the Executioner books, surely.” The writing is a little thicker, a little richer than you get in the least of the Mack Bolan books. However, there was some foreshadowing that all was not right. I, or someone else, must have given this book of poems purrportedly by cats to my beautiful wife. When she was culling her office books, she was looking to get rid of it (so I hope it was a gift from someone else, because I’d like to think she treasures things I give her beyond their actual worth). So I picked it up as something I could easily browse during football games.

I, or someone else, must have given this book of poems purrportedly by cats to my beautiful wife. When she was culling her office books, she was looking to get rid of it (so I hope it was a gift from someone else, because I’d like to think she treasures things I give her beyond their actual worth). So I picked it up as something I could easily browse during football games. You’re taking a look at my recent reading and note that I bought all of these books within the last two weeks, and you think, “Hey, Brian J., wouldn’t it be better to have only bought these three or four books, read them, and then buy a couple more instead of buying dozens at a crack, dozens of times a year ensuring you have a backlog of thousands of books that you don’t have lifetime enough left to read them all?” I supposed that would be one way to do it, gentle reader. But allow me to answer with a question of my own: Why do you have so little faith in medical science?

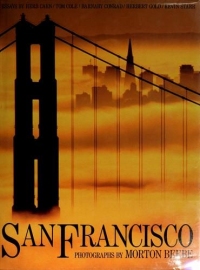

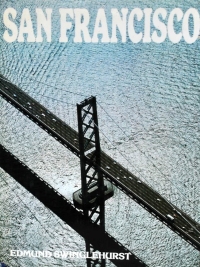

You’re taking a look at my recent reading and note that I bought all of these books within the last two weeks, and you think, “Hey, Brian J., wouldn’t it be better to have only bought these three or four books, read them, and then buy a couple more instead of buying dozens at a crack, dozens of times a year ensuring you have a backlog of thousands of books that you don’t have lifetime enough left to read them all?” I supposed that would be one way to do it, gentle reader. But allow me to answer with a question of my own: Why do you have so little faith in medical science? In the battle between the San Francisco picture books between this book and

In the battle between the San Francisco picture books between this book and  This book is a picture book of San Francisco from 1979.

This book is a picture book of San Francisco from 1979.  As

As  This book is a coffee table sized book of small trivia bits about the presidents (through Ronald Reagan, although someone helpfully appended Bush, Clinton, and Bush in pen at the end of one list). The material is not sourced, and it’s not reliable–two separate vignettes give different stories about Ulysses S Grant’s name (one is that he has no middle name; the other is that he became US Grant when someone filled out his application to West Point incorrectly, not using his real name, Hiram Ulysses Grant). And this is a later edition of the book, which was first published in 1972, so some things have been updated to reflect the new presidents (Ford, Carter, and Reagan), but some of them have not.

This book is a coffee table sized book of small trivia bits about the presidents (through Ronald Reagan, although someone helpfully appended Bush, Clinton, and Bush in pen at the end of one list). The material is not sourced, and it’s not reliable–two separate vignettes give different stories about Ulysses S Grant’s name (one is that he has no middle name; the other is that he became US Grant when someone filled out his application to West Point incorrectly, not using his real name, Hiram Ulysses Grant). And this is a later edition of the book, which was first published in 1972, so some things have been updated to reflect the new presidents (Ford, Carter, and Reagan), but some of them have not. I picked up this book right after reading

I picked up this book right after reading  After reading

After reading  Earlier this year, Friar called John Norman’s work

Earlier this year, Friar called John Norman’s work  This book is a scientifically funny book. You can take a look at it, and you can see the satire within it and the quips and the proven turns-from-reality that make for humor.

This book is a scientifically funny book. You can take a look at it, and you can see the satire within it and the quips and the proven turns-from-reality that make for humor. This book was in the Bookmarx philosophy section, and I didn’t know why when I started. I bought it because I’ve been reading some philosophical material of late, and this book is pretty thin, so it would be (I hoped) a quick read in that line.

This book was in the Bookmarx philosophy section, and I didn’t know why when I started. I bought it because I’ve been reading some philosophical material of late, and this book is pretty thin, so it would be (I hoped) a quick read in that line. As I mentioned, I picked up this book

As I mentioned, I picked up this book  As you might remember, gentle reader, I read Klein’s

As you might remember, gentle reader, I read Klein’s  As I mentioned in my most recent review of an Executioner book (

As I mentioned in my most recent review of an Executioner book ( This is a mild little humorous book about renovating or doing projects about your home with your spouse. Basically, the author recounts stories from friends and her own life, sometimes in a manner of paragraphs and sometimes just a sentence or two. The anecdotes are grouped in chapters by renovation and project type, like painting, wallpapering, plumbing, working with contractors, and so on.

This is a mild little humorous book about renovating or doing projects about your home with your spouse. Basically, the author recounts stories from friends and her own life, sometimes in a manner of paragraphs and sometimes just a sentence or two. The anecdotes are grouped in chapters by renovation and project type, like painting, wallpapering, plumbing, working with contractors, and so on. I picked up this book at the Fair Grove branch of the Springfield-Greene County Library. You’re saying to yourself, “Hey, has he run out of books to read in his own library and the more local branches of his local library so that he has to drive almost an hour to find something new?” No, gentle reader; this summer, my boys and I are trying to visit each branch of the Springfield-Greene County library, and when we got to the Fair Grove branch (a small room off of the Fair Grove City Hall), I spotted this book in the one shelf of philosophy/religion/magick whilst my children were picking out books of their own. As I’m interested in learning more about how the Bible was compiled over time, I thought it would be a great place to start.

I picked up this book at the Fair Grove branch of the Springfield-Greene County Library. You’re saying to yourself, “Hey, has he run out of books to read in his own library and the more local branches of his local library so that he has to drive almost an hour to find something new?” No, gentle reader; this summer, my boys and I are trying to visit each branch of the Springfield-Greene County library, and when we got to the Fair Grove branch (a small room off of the Fair Grove City Hall), I spotted this book in the one shelf of philosophy/religion/magick whilst my children were picking out books of their own. As I’m interested in learning more about how the Bible was compiled over time, I thought it would be a great place to start.