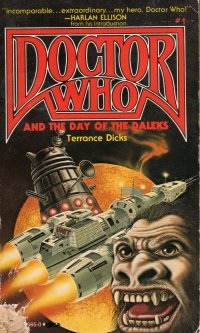

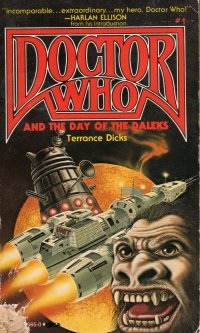

I got this book in 2015, which was far after any semblance I had of Doctor Who fandom.

I got this book in 2015, which was far after any semblance I had of Doctor Who fandom.

As I might have mentioned (briefly, in in 2011, before I bought this book), Doctor Who played on Sunday nights at 10:30 on the St. Louis PBS station (followed by Red Dwarf, which I was talking about in 2011). Of course, my bedtime in the trailer days was 9:00, so I didn’t watch it live, but I did record them on videocassettes. Initially, I think that I only started recording them when we lived down the gravel road, but I have a lot of videocassettes (of course I still do) from that era, and when I was in the creative writing class probably my sophomore year of high school I wrote a series of short stories wherein the main character steals the TARDIS, so I was already familiar with the program in 1987 or so. I haven’t rewatched the videocassettes in a long time–I tried watching a program when my boys were children, but the first episode featured a plot where people were getting attacked by people in the sewers, which meant that they did not hardly see Colin Baker on the screen before someone went into (grainy videocassette recording) darkness and screamed, and that was all they could take–the oldest had an imagination full of darknesses which he might have outgrown (even as his father has not). Perhaps I’ll use this as an excuse to rewatch some of those old videocassettes. And perhaps the Red Dwarf box set I got in 2011.

One more Doctor Who memory, gentle reader, if you will indulge me. When I was at the university, I was not watching the show because it was not available in Milwaukee as I was aware (nor St. Louis when I returned). I made the acquaintance of Doctor Comic Book when we were in the English program at the University, he a year behind me. We got to be…. Acquaintances, I suppose, but close enough that he let me stay at his apartment on the East side one night my senior year when I attended a party that ended after the buses stopped running. And in the months (years) after college, when I was travelling to Milwaukee monthly (and later a couple times a year, but quite often), he let me stay with him for the weekend. One night, alone in his apartment (well, there with my college crush, who was not at all interested in me, of course), I opened one of his closets to discover a stack of old Doctor Who paperbacks, with this one probably on top (as it is the first in the American paperbacks). I teased him about it, saying, “That explains it!” as he favored long coats and a long scarf. He chuckled guiltily. He would later really get a doctorate and teach courses in comic book rhetoric when we reconnected on Facebook, as happened in the early years of this century, and then parted in political acrimony, as happened in later years of the century. Still, this paperback makes me think of the fellow as well as being young once.

So this is the first American paperback in the line, although Britain had seen numerous Doctor Who tie-ins before then, but I guess in the late 1970s, the show had made some appearances in America (given that, what, six or seven years later I saw it). This book tells a story from the third Doctor, played by John Pertwee (years as the Doctor: 1970-1974). That’s back when the Doctor was in England for an extended period as he tried to work on the TARDIS and helped the Brigadier and UNIT (United Nations Intelligence Taskforce).

An aging diplomat is to chair a conference to avert a war as tensions between the West, the Soviet Union, and China are boiling over. He leaves his estate for China, and when he does, a group of rebels from a future where the Daleks have taken over the Earth return, certain that their goal is to kill the diplomat whose actions lead to their dystopian future. The Doctor is less certain about what triggers the war that diminishes humanity and leads to the Dalek dominion–what if their success caused it? So we have (one can tell low budget even from the prose) scenes in the dystopian future and (one can tell low budget even from the prose) scenes on the estate as the Doctor tries to rescue his companion, taken to the future, and to avert a Dalek assault on the compound when the diplomat returns with dignitaries of the hostile nations.

Terrence Dicks was a writer for the show, so he was working with actual scripts, so the story probably pretty well matches what one would have seen on the BBC when I was lying nude on rugs for photographs (gentle reader, I assure you, this was when I was young, before I turned fifty). Rumor has it (and by “rumor,” I mean some Doctor Who fan site I read after reading this book but which I didn’t save in a tab until I wrote this, and I am too lazy to post it for you, oh, all right, it might have been this one or something that scraped it) that Pertwee didn’t like the episode that much at first, but, c’mon, man: it was 1970s television. In Britain. Nobody expected much more until Thatcher came to power, and to be honest, not much more after that. And by “nobody,” I mean “Americans.”

At any rate, it’s a quick 139 page read which, like all other paperbacks of the era, talked about other series the publishers had going at the time. Instead of Deadlands books, though, this one promotes a series called Blade, which was like a Deadlands with a timelord in it.

Man, if I put some effort into it (and, you know, had good guaranteed employment in the future whose base pay could keep up with base Biden-economy expenditures), I would like to be a serious collector of these old paperbacks. But I am not likely to find myself much in the paperback sections of the big book sales. Although one never knows what the future or the possible future saved by the intervention of a British television science fiction series might lead to. Who knows? I might even reconcile with Doctor Comic Book when I and my clan are driven north by the invading hordes and we take refuge on the shores of Lake Superior and reluctantly have to liberate the fortified campus from what they voted for.

This book is one of two that I bought by this local author in Heber Springs, Arkansas last year.

This book is one of two that I bought by this local author in Heber Springs, Arkansas last year.

After watching

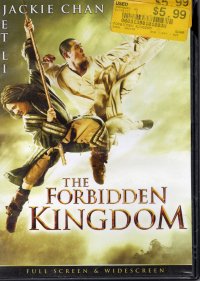

After watching  When it came time to delve back into the movies in or on the to-watch media center, I picked up this film. It must have looked interesting to me, as I bought it twice last year: once at the library book sale

When it came time to delve back into the movies in or on the to-watch media center, I picked up this film. It must have looked interesting to me, as I bought it twice last year: once at the library book sale  If I had found this book in time for the

If I had found this book in time for the

After discoursing, briefly, on

After discoursing, briefly, on  It seems like I just watched the first two films in this series, gentle reader, but I watched

It seems like I just watched the first two films in this series, gentle reader, but I watched  After watching the Indiana Jones movies

After watching the Indiana Jones movies  This film came out back when we still went to films in the theater–we were still in Casinoport. I had just started working as a consultant for the digital agency, starting my own consulting company and working from home for the first time. Basically, I’ve worked from home ever since except for a year or so when the agency hired me and had an office downtown. Perhaps that was not a film-filled summer–I was not only working full time for the agency, but I’d picked up short contracts with previous employers for in-office night work and white paper writing. So I had knowledge of the film when it came out and since–Foxx was something then, ainna? His Oscar winning turn as Ray Charles would come out a couple months later–and Cruise was in the mid-career doldrums, although his doldrums tended to move better than actual doldrums.

This film came out back when we still went to films in the theater–we were still in Casinoport. I had just started working as a consultant for the digital agency, starting my own consulting company and working from home for the first time. Basically, I’ve worked from home ever since except for a year or so when the agency hired me and had an office downtown. Perhaps that was not a film-filled summer–I was not only working full time for the agency, but I’d picked up short contracts with previous employers for in-office night work and white paper writing. So I had knowledge of the film when it came out and since–Foxx was something then, ainna? His Oscar winning turn as Ray Charles would come out a couple months later–and Cruise was in the mid-career doldrums, although his doldrums tended to move better than actual doldrums.

Wow, this book is almost thirty years old. I bought it at some point since then–the historical records (the blog here) are incomplete as to when, but the copy I have is a hardback without the dustjacket and has only the price marked in pencil on the frontspiece. The book, he acknowledges a with a smirk, is a bit of a money grab based on the popularity of his television show The Drew Carey Show during the Clinton administration.

Wow, this book is almost thirty years old. I bought it at some point since then–the historical records (the blog here) are incomplete as to when, but the copy I have is a hardback without the dustjacket and has only the price marked in pencil on the frontspiece. The book, he acknowledges a with a smirk, is a bit of a money grab based on the popularity of his television show The Drew Carey Show during the Clinton administration.

I got this book

I got this book