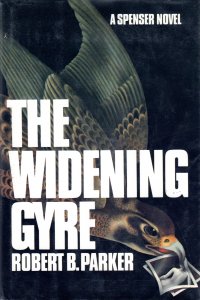

Of course I read this book right away after buying it last weekend. It’s just about the only fiction I bought, as I don’t tend to browse those tables at large book sales. But this was on the Collectibles/Antiquarian tables as it’s a signed first edition from 1983. Which makes it both.

Of course I read this book right away after buying it last weekend. It’s just about the only fiction I bought, as I don’t tend to browse those tables at large book sales. But this was on the Collectibles/Antiquarian tables as it’s a signed first edition from 1983. Which makes it both.

Also, I should note that right about the turn of the century, I read through the Robert B. Parker books in order to that point. It was before I was blogging and before I was writing book reports, so I don’t have any way to review what I thought about them then. But twenty years later, with the early twenty-first century Parkers and the Atkins/Brandman/Coleman continuation of Parker’s series between now and then, I am putting my thoughts down which are only a little about the book and more about the oeuvre and its impact on my youth. I’ve mentioned it before (see my thirty-year-old essay Meeting Robert B. Parker), gentle reader, but all those people coming in from Google in the coming years won’t have heard the story a hundred times before.

So, where are we in the series? Susan has gone off to Washington to work. So it’s before Valediction when she goes out west. And before A Catskill Eagle and before the television series, which I think influenced his work to where the books later become mostly dialog and repeats.

At any rate, the plot: A congressman and Senate candidate comes to Spenser because he needs a head of security, and Spenser’s at loose ends so he hires on. He discovers someone is blackmailing the congressman to drop out and endorse his opponent. The congressman’s wife apparently likes to drink and has ended up videotaped having sex with a younger man. Spenser vows to find out who did it and how to extricate the congressman without exposing his wife or even letting the wife know what is going on. Because the congressman love-loves his wife, you see. Or maybe that should be capitalized as Love because their relationship is drawn to parallel Spenser and Susan’s. Spenser discovers that the son of local mobster Joe Broz, Gerry Broz, is doing a little dealing and grifting on his own to impress his father, and when things go a little sideways, the son asks his father’s second to help clear it up without the father’s knowledge.

When analyzed kind of like I do the Executioner books, I break it into a couple set pieces of actual detecting between sections of self-analysis and conversations with the other characters, and I see how few action set pieces there actually are. Of course, the book clocks in at under 200 pages, so it’s not a Jack Reacher or other modern suspense novel–and it owes as much to John D. MacDonald as it does to Raymond Chandler or Ross MacDonald. But the pieces fit all right together with a balance between them which added deft depth to the genre.

As I read this, I recognized why I loved these books as a kid. They’re suspense novels, with the Spenser being arch and tough and well-read and philosophical, musing (again) on self-definition and introducing some conceptions on what means for Spenser to Love (or love-love) Susan. The kind of thing that a boy growing up without a father and prone to reading books might come to idolize.

Ah, but the seeds of the things that later turned me off to Spenser novels are present. The introspection on what love is and how it can best serve Feminist-driven female self-discovery zeitgeist (here only the woman being free to be herself whilst Spenser Loves or love-loves her). Although the MacGuffin of the congressman’s wife’s infidelity here is treated not so much as that it’s morally wrong but impractical and possibly neurotic, it would be almost thirty years before it would be something to celebrate (as in the repellent Split Image). We also get the starts of Deus Ex Mafia, where the resolution is a negotiated settlment between Spenser and some crime figure who comes to believe, possibly after an attempted hit, that coming to terms with Spenser is easier and safer than killing him. I guess the negotiated settlements started out earlier–God Save the Child and Early Autumn come to mind–but in later novels, negotiated settlements with actual criminals seem to become the norm. Or maybe I don’t remember them as well because I did not read them in my formative years and because I only read them once.

On one hand, reading this book reminded me of why I liked the earlier Spenser novels and almost makes me want to re-read them up to maybe Valediction. I mean, I re-read Early Autumn fairly regularly in my formative years and even gave it as a gift to one or more friends that I thought could use some encouragement in self-definition.

But I have so many other books to read, so I will likely hold off on that unless I find other signed first editions on collectible tables in the future.

As it stands, the hardback I already owned of this title was a Book Club Edition. So I seriously upgraded my collection with this $7.50 purchase. Which could well be my last addition to the collection unless the Spenserian Sonnet limited edition falls into my lap. I see that the Wikipedia entry for Robert B. Parker’s bibliography does not include his dissertation The Private Eye in Chandler and Hammett or Parker on Writing, both signed and numbered limited editions nor his signed and numbered sonnet; I have two of three in my collection as I was a serious collector for a while around the turn of the century. But, ah, the loss of heroes, ainna?

Depending on the day, I rank this one above or below “A Savage Place” in that first arc of books that roughly winds up at “Catskill Eagle.” Obviously no one likes their heroes to fail the way Spenser did in “Place,” but “Gyre” seems like a puzzle with pieces jammed instead of fitted together. Meade and Ronnie are written like they’re supposed to have real depth but they’re very much sterotypes – and they don’t even really fit as Spenser/Susan projections since the unfaithful partners in the relationships are reversed.

Although, “I’m with the clean mouth bureau. Step around the corner here and I’ll explain why swearing is ignorant” is in my top tough-guy quips file.

You know, reading these through the lens of where the series went and where the entire genre went might lead one to wonder if we’re looking back at it with a golden glow. I don’t think so–it is that good, and it does stand out among other examples of the genre.

One wonders whether Raymond Chandler himself would have held up if his books had extended beyond the half dozen he completed, or if Dash Hammett had tried to write at the novel length over a long period of time.

Not everyone can be John D. MacDonald.

I think the Houghton-Mifflin/Delacorte period has some of the best of the genre, period. Even Parker’s fouls had stuff in them better than whole alphabetical sections from the rest of the shelves. Once he had his shakedown cruise in “Godwulf Manuscript” he shed his over-reliance on some of the tropes, trimmed his word count and was off to the races.

When he went to Putnam it seemed like he spent more and more time coasting. For my money, “Playmates” is about the only one from that run that can stand up to the best of the first 10-12 years. “Painted Ladies” comes close, as if he recognized that each book might be his last and he thought he should try harder to make a good closing statement.

I re-read the early books in the early part of the century, in the years B.B. (before the blog), but I haven’t re-read them since–which is odd, since the millennial re-read was not the first time I’d returned to them.

I put the marker at A Catskill Eagle, as you know, which coincided with his time in Hollywood. The other things dropped off from there. If I had to point to one that I thought was almost okay from there, it might have been Double Deuce. But I would have said it was the Early Autumn equivalent for Hawk that turned out about how it could. Also, I grew up for a time in a housing project where the basketball nets were chain–when they weren’t missing.

So I am not going to keep up with you talking intelligently about the change and direction of the series book-by-book as they sort of blend together after the time where he drew the titles from poems.

Speaking of which, I thought about titling my first (unpublished) novel A Sordid Boon following this guidance; instead, I titled the manuscript Marquette Minus One.

Re-reading this book, though, makes me want to re-read the early works again–they inspired me to write, and to be honest, I could do with some inspiration again, as my creative writing aside from the tappings here has stalled out.