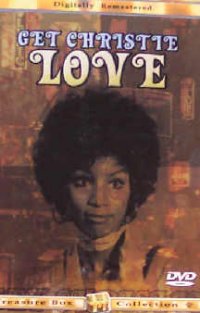

I don’t know where I bought this collection, but it looks to be fifteen films from the Blaxploitation era of the 1970s. And, to be honest, they’re not the best of them–one bets you could sell Shaft, Across 110th Street, Foxy Brown, Superfly, and a handful of other films singly–heck, I bought Get Christie Love! on a dollar DVD close to twenty years ago. But, you know, as I got into them, I discovered that they’re not so much Blaxploitation films as films with black casts.

I don’t know where I bought this collection, but it looks to be fifteen films from the Blaxploitation era of the 1970s. And, to be honest, they’re not the best of them–one bets you could sell Shaft, Across 110th Street, Foxy Brown, Superfly, and a handful of other films singly–heck, I bought Get Christie Love! on a dollar DVD close to twenty years ago. But, you know, as I got into them, I discovered that they’re not so much Blaxploitation films as films with black casts.

As I’m going to drop a couple lines on each of them, I will tuck them below the fold.

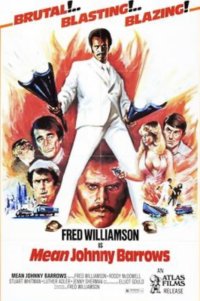

Mean Johnny Barrows (1976) begins when Barrows, in the army, is leading a training exercise where he steps on a live mine. A couple of white soldiers, one a superior officer, come up to him and talk smack to him about it. He defuses the mine–well, puts it back into safe mode–and then punches his superior officer leading to his (Barrows’) dishonorable discharge. He returns home, but is mugged getting off the bus and is hauled in by cops who think he is drunk. He gets a hand out from an Italian restaurant owned by mafiosos, and the son recognizes him from his football days at school. He is offered a job working for the mob, but turns it down and finds work at a gas station instead. When a rival mob gang wipes out the family who offered Barrows the work and when the wife of the son for whom Barrows has an unrequited love is “kidnapped,” he goes into action using the skills he used in the military to even the score. At the end, he learns the wife was in on the whole thing, and the film ends when she steps on a landmine he has planted at their last meeting, and they both die in the blast.

Mean Johnny Barrows (1976) begins when Barrows, in the army, is leading a training exercise where he steps on a live mine. A couple of white soldiers, one a superior officer, come up to him and talk smack to him about it. He defuses the mine–well, puts it back into safe mode–and then punches his superior officer leading to his (Barrows’) dishonorable discharge. He returns home, but is mugged getting off the bus and is hauled in by cops who think he is drunk. He gets a hand out from an Italian restaurant owned by mafiosos, and the son recognizes him from his football days at school. He is offered a job working for the mob, but turns it down and finds work at a gas station instead. When a rival mob gang wipes out the family who offered Barrows the work and when the wife of the son for whom Barrows has an unrequited love is “kidnapped,” he goes into action using the skills he used in the military to even the score. At the end, he learns the wife was in on the whole thing, and the film ends when she steps on a landmine he has planted at their last meeting, and they both die in the blast.

The film is the baby of Fred Williamson who starred and directed. Williamson was the a former football player who should go onto my pantheon of mid-century football players who transitioned to actors.

However, the film turns on a couple of less-than-realistic moments. The beginning, where he steps on the landmine and the ones who planted it as a dangerous prank or attempt to rub him out come up to him and taunt him about it. Then, when he returns home, he has no family, no friends, and although he was a star football player, no support network. And he’s pretty much a pawn throughout the film, and the ending with the landmine, although I can see why the writer liked circling around to the beginning, but, c’mon, where did he get that landmine?

The film also has appearances by Elliot Gould and Roddy McDowall.

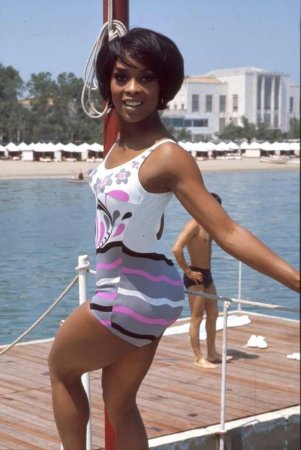

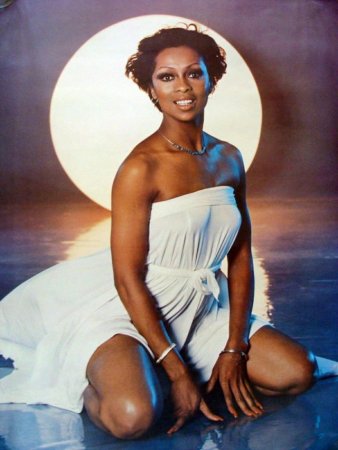

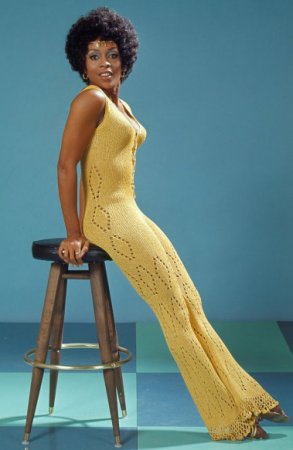

Lady Cocoa (1975) stars Lola Falana as the girlfriend of a Harlem mobster looking to move into the rackets in Nevada. She is in prison for contempt of court for a long time but is sprung when she agrees to testify against him. The film tells the story of her one day of freedom at a casino hotel under the guard of an older white detective and a young black patrolman put into a suit for the guard duty.

Lady Cocoa (1975) stars Lola Falana as the girlfriend of a Harlem mobster looking to move into the rackets in Nevada. She is in prison for contempt of court for a long time but is sprung when she agrees to testify against him. The film tells the story of her one day of freedom at a casino hotel under the guard of an older white detective and a young black patrolman put into a suit for the guard duty.

It’s best to think that this is the film of that young black detective, played by Gene Washington, who opens up a bit as Lady Cocoa goads him into having some fun. Because, honestly, the Lady Cocoa character is annoying–she’s at turns manipulative, spoiled, and child-like, throwing tantrums until she gets what she wants. Perhaps she’s a bit on the manic pixie girlfriend scale, but I did not find her endearing at all.

At the end of it all, we learn that her “boyfriend” has put a hit on her to prevent her from testifying, not believing the promised testimony was her ruse to get out of prison for a single day.

At any rate, the film stars Lola Falana. You know, in 2023, I did not recognize the name, but she has had quite a career. In addition to starring in this movie, she played in numerous others and appeared on television shows and variety shows of the era. She also had a residency in Las Vegas for a while and, according to Wikipedia still lives there and works in Christian ministry.

An interesting story, her life. Unfortunately, the character in this movie, as I said, was not ideal.

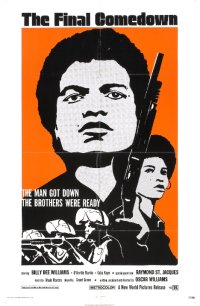

The Final Comedown (1972) stars Billy Dee Williams as the leader of a radical group in a shootout with the police. The story starts with the shootout occurring and then weaves in a number of flashbacks that I guess are supposed to show how the main character became radicalized and ultimately violent–run ins with the police, being turned down for a job because he’s black (after being told he was hired for the job) and so on. But the flashbacks also, and early on, just show the character as angry, yelling at his white lover (the child of privilege who is down with the cause) while she offers platitudes–the scene is very clunky and drips with buzzwordery and not real human emotions. The character also yells political slogans at his own mother while she’s feeding him dinner.

The Final Comedown (1972) stars Billy Dee Williams as the leader of a radical group in a shootout with the police. The story starts with the shootout occurring and then weaves in a number of flashbacks that I guess are supposed to show how the main character became radicalized and ultimately violent–run ins with the police, being turned down for a job because he’s black (after being told he was hired for the job) and so on. But the flashbacks also, and early on, just show the character as angry, yelling at his white lover (the child of privilege who is down with the cause) while she offers platitudes–the scene is very clunky and drips with buzzwordery and not real human emotions. The character also yells political slogans at his own mother while she’s feeding him dinner.

The flashbacks also talk about the plan that the character cooks up with some white radicals who–I don’t know, don’t hold up their end of the deal? I’m a little unclear on the plan or the goal of the event that leads to the shoot-out, nor am I clear as to what the character hoped would happen. Revolution?

I really wanted more depth out of the character. He has some sympathetic moments, but they are really overshadowed by the anger. I really wanted some kind of For Whom the Bell Tolls moment, some sympathy with the character, but I could not. Strangely enough, fifty years on, I don’t think we’ve moved past the anger.

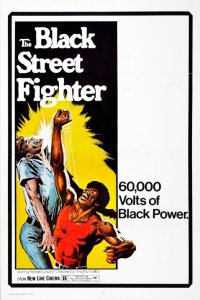

The Black Street Fighter (1075), also known as Black Fist or Bogard, could be compared to Every Which Way You Can although the latter came out in 1978 after this movie. At any rate, Richard Lawson portrays Leroy Fisk who takes work participating in an underground bare knuckle no-holds-barred streetfighting ring where when he wins, he gets a cut of his handler’s winnings. A corrupt cop (played by Dabney Coleman) wants his share, and an underworld figure wants his share, too. When Fisk wants out, he has to do one last fight to secure financial, erm, security and to get the ticks off of his back.

The Black Street Fighter (1075), also known as Black Fist or Bogard, could be compared to Every Which Way You Can although the latter came out in 1978 after this movie. At any rate, Richard Lawson portrays Leroy Fisk who takes work participating in an underground bare knuckle no-holds-barred streetfighting ring where when he wins, he gets a cut of his handler’s winnings. A corrupt cop (played by Dabney Coleman) wants his share, and an underworld figure wants his share, too. When Fisk wants out, he has to do one last fight to secure financial, erm, security and to get the ticks off of his back.

A better story than the others so far as the main character is still a bit of a pawn but has enough agency to act as his own man.

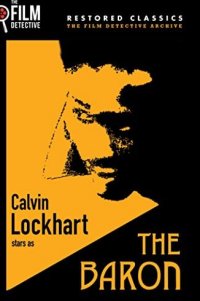

The Baron has Calvin Lockhart as Jason, a man who has started making a film starring himself as Baron von Tripp, a race car driver and debonair aristocrat. He’s almost finished with it, but needs a little more money, so he shows the progress to his backer, a drug dealer called Cokeman (for some reason) who rebuffs the capital call and tells Jason he wants his $300,000 investment back immediately. Jason tries to sell the property to a contact in California, but it would come with some strings–that the film be rewritten to feature white actors, and he is to be eliminated from production entirely. So he refuses.

The Baron has Calvin Lockhart as Jason, a man who has started making a film starring himself as Baron von Tripp, a race car driver and debonair aristocrat. He’s almost finished with it, but needs a little more money, so he shows the progress to his backer, a drug dealer called Cokeman (for some reason) who rebuffs the capital call and tells Jason he wants his $300,000 investment back immediately. Jason tries to sell the property to a contact in California, but it would come with some strings–that the film be rewritten to feature white actors, and he is to be eliminated from production entirely. So he refuses.

Which puts him and Cokeman in a bind as the underworld figure, played by recognizable bad guy Richard Lynch who is Cokeman’s boss is not pleased that Cokeman put his money into a film. So he applies pressure to both and eventually gets his hooks into Jason for large sums of money provided by Jason’s sugar mama, an aging starlet played by aging starlet Joan Blondell. This leads to a quick resolution and a happy ending which is a bit uncharacteristic of many of the films on the first side of the first disc.

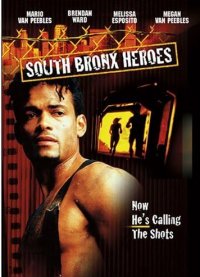

South Bronx Heroes (1985) really departs from what I thought was the theme of this set. It’s more like an after-school special than a Blaxploitation film, and of the cast, really only Mario Van Peebles and his sister Megan (who plays his sister in the film) are black.

South Bronx Heroes (1985) really departs from what I thought was the theme of this set. It’s more like an after-school special than a Blaxploitation film, and of the cast, really only Mario Van Peebles and his sister Megan (who plays his sister in the film) are black.

At any rate, white foster parents in the suburbs are using the foster kids to make child, well, you know, and when the foster father tells one of the little girls that they will have to separate her from her older protective brother, the brother and sister (not Mario Van Peebles and his sister) run away with photos as evidence. Meanwhile, Tony (Van Peebles) makes his way home after serving time in a Mexican prison. He outwits some local toughs who want to rob him and makes his way to his childhood home, an apartment now held by his sister, and learns that his grandfather has passed away.

When the runaways (the brother and sister, not the band featuring Joan Jett, Lita Ford, et al) break into the apartment to shower and steal food, they accidentally leave behind the photos. When the brother returns to retrieve them, Tony catches him and they set up a plan to get money or exact justice–one is not sure until the ending.

The film is told partially in flashback and is rather thin for the running time, but the film makes up for it with long, dramatic shots of the abandoned buildings and rubble of the South Bronx. An accomplice of the foster parents (the guy who killed the runaways’ father?) combs the neighborhood for them, but there’s no drama in it as he never gets close to finding them. He just drives around and asks people, allowing for more visuals of the South Bronx.

Frankly, it doesn’t fit in with what I thought was the theme of this set, but apparently the actual theme is becoming “movies with black people in them.”

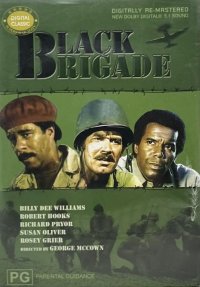

Black Brigade (1970) originated as an Aaron Spelling television move originally called Carter’s Army which should give some insight into the original slant of the film or goal of the film.

Black Brigade (1970) originated as an Aaron Spelling television move originally called Carter’s Army which should give some insight into the original slant of the film or goal of the film.

In World War II, a Captain Carter (a white guy) is given the order to take command of a company and to lead a mission to secure a dam and prevent the Germans from blowing it and impeding the Allied advance. He finds that the company to which he has been assigned is a support unit completely of black men who don’t act according to his idea of soldiers. He takes a small group of them, including the Lietenant (Robert Hooks) and privates played by Richard Pryor, Rosey Grier, Moses Gunn, Glynn Turman, and Billy Dee Williams, on the mission and learns respect for them as individuals, but not all of them survive.

Originally cast as Carter’s War, the message would have been one of the white captain’s learning to respect his black fellow men. However, retitling it shifts the focus to the company. Which is all right, I suppose, as they’re as important as the captain. Oh, well. Most of the films in this set have been released under multiple titles in different formats. But although this one is definitely action, it is not urban at all. So after an after-school special, we have a war picture.

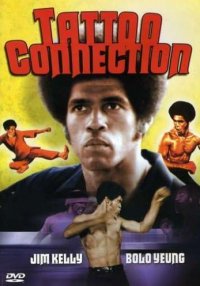

Tattoo Connection (1978) is a Hong Kong martial arts film starring Jim Kelly, a black martial artist who appeared in Enter the Dragon with Bruce Lee and then starred in a handful of other films, including one called Black Belt Jones which is why this film is sometimes billed as Black Belt Jones 2 even though it is unrelated.

Tattoo Connection (1978) is a Hong Kong martial arts film starring Jim Kelly, a black martial artist who appeared in Enter the Dragon with Bruce Lee and then starred in a handful of other films, including one called Black Belt Jones which is why this film is sometimes billed as Black Belt Jones 2 even though it is unrelated.

In it, Kelly plays Lucas, an American insurance investigator looking for a diamond stolen by a syndicate run by martial arts expert Lu. Lu’s second Tung Hao is in love with a stripper named Nana whom Lu sometimes uses and Lucas takes a fancy to. We have a number of set pieces where the gang tries to eliminate Lucas, but also a rift grows between Tung Hao and Lu over whether Tung Hao and Nana can ever leave which leads to a clash between the two. And Lukas, of course.

Man, a throwback for me, as we used to stay up on Saturday nights for Kung Fu Action Theater after MASH and Hawaii Five-O to see dubbed movies like this. But studying martial arts has ruined these films for me, as I’m constantly offering advice to the fighters. “Don’t lead with a spin kick! You can see it coming!” “Stick to stick, flesh to flesh, never flesh to stick!” “Don’t stand in the middle of multiple attackers–stack them!” And so on.

Also, I had to watch this film with one finger on the Next button on the remote. I haven’t invited my boys to join me for these films, as I would not want to see what scandalized them most: the baddest word applied liberally or the breasts which appear in most of them. Well, this film had several scenes with full frontal female nudity, and I was prepared to be scandalized if someone else in the family walked through the room during one such scene. Fortunately, not. And as to the presence noted herein, let’s keep that between you and I, gentle reader.

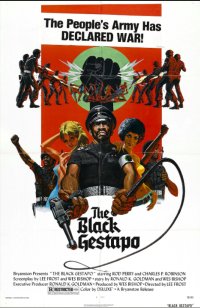

The Black Gestapo (1975) tells an interesting story. Rod Perry plays General Ahmed who runs The People’s Army which, despite the name, is more of an aid society providing food and health services to underserved citizens of Watts. They run up against (white) mafiosos running numbers, prostitution, and drugs in the ghetto, and after the rape of one of the army’s nurses–and Ahmed’s on-again/off-again lover–he authorizes his more militaristic underling, Colonel Kojah (played by Charles Robinson) to create a small trained force for protection.

The Black Gestapo (1975) tells an interesting story. Rod Perry plays General Ahmed who runs The People’s Army which, despite the name, is more of an aid society providing food and health services to underserved citizens of Watts. They run up against (white) mafiosos running numbers, prostitution, and drugs in the ghetto, and after the rape of one of the army’s nurses–and Ahmed’s on-again/off-again lover–he authorizes his more militaristic underling, Colonel Kojah (played by Charles Robinson) to create a small trained force for protection.

Kojah has other ideas, on the other hand–he trains far more in military tactics and training, and then pushes the mafia out and takes over their rackets. He buys a large (3 acres) compound to turn into a combination party pad/training camp and redesigns the uniforms to look more frightening (and Nazi-like). When Ahmed finds out, he plans an Executioner-style one-man raid on the compound to confront his underling.

It’s a pretty good movie, and it does raise the question as to whether militant black movements would turn out to be a case of “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” I would normally quibble with the “giant” size of a 3-acre-lot, but recent research on unrelated matters has led me to review real estate listings in Beverly Hills, and what I saw was astounding: These enormous houses with the occasional swimming pool or tennis court, but the next house is just a couple hundred feet away. I mean, look at this listing:

It’s a 14,000 square foot house on 1.84 acres. And it’s within shouting distance, or just loud talking distance of its neighbors.

And because that house is big and expensive, it’s actually in a less-dense area. So, yeah, you’re not going to have paramilitary training going on there without the neighbors hearing it.

Blaxploitation? A closer representative of the genre than The Black Brigade, but some reviews quibble with the message that black gangsters are not black power, just gangsters.

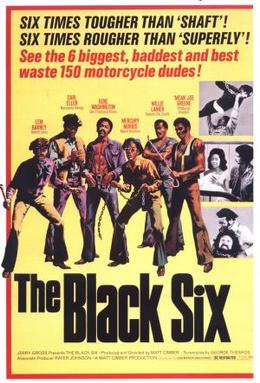

The Black Six (1974) features not just one, but six football players in the title roles and other football players and baseball players in it. Gene Washington (San Francisco 49ers), Joe Green (Pittsburgh Steelers), Eugene Morris (Miami Dolphins), Lem Barney (Detroit Lions), Willie Lanier (Kansas City Chiefs), and Carl Eller (Minnesota Vikings)–their football teams are identified in the opening credits–play six Vietnam veterans who ride together to see the country or just to be free. When one’s brother, a high school football player, is murdered by a white biker gang because he was dating the sister of the bike gang leader. So the Black 6 return to Bubba’s home town to look into it.

The Black Six (1974) features not just one, but six football players in the title roles and other football players and baseball players in it. Gene Washington (San Francisco 49ers), Joe Green (Pittsburgh Steelers), Eugene Morris (Miami Dolphins), Lem Barney (Detroit Lions), Willie Lanier (Kansas City Chiefs), and Carl Eller (Minnesota Vikings)–their football teams are identified in the opening credits–play six Vietnam veterans who ride together to see the country or just to be free. When one’s brother, a high school football player, is murdered by a white biker gang because he was dating the sister of the bike gang leader. So the Black 6 return to Bubba’s home town to look into it.

We have a number of set pieces where the fellows help out a white, presumably widow, farmer; where Bubba returns home to his mother and Black Power sister (getting ready for college) who spouts bromides but eventually very humanly worries for her brother, meeting up with an old flame who has been turned out as a prostitute, meeting the indifferent detective on the case, meeting the sister who was dating the brother, confronting the bike gang who killed the brother, and an eventual climactic battle with the biker gang and another, larger gang that they called for reinforcements (led by a recently retired football player).

The ending is a bit ambivalent–a bunch of fire and explosions–which made me think something was missing from the transfer I watched–but apparently (or so Wikipedia asserts) the film was scheduled to end with the deaths of all of the Black Six, but the actors protested the original ending, which led to the ambiguous ending with text asserting that the Black Six might return. No sequel was filmed, however.

At any rate, another enjoyable movie with a fairly good story arc and with the characters relatively well-developed without being mere ciphers for viewpoints.

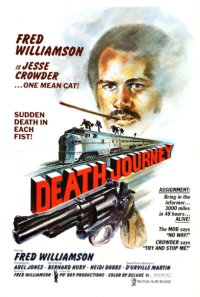

Death Journey (1976) tells a familiar tale: A witness for a mob trial needs to get from Point A to Point B in a short time frame, and there’s only one man to do it. In 1977, it was Clint Eastwood in The Guantlet. In 2006, it was Bruce Willis in 16 Blocks. In 1975, it was Fred Williamson in his first (of five) turns as Jesse Crowder, a private investigator who used to be a cop but did things his way. The DA in New York reaches out to him and has him bring a mob accountant from L.A. to New York in 48 hours to testify.

Death Journey (1976) tells a familiar tale: A witness for a mob trial needs to get from Point A to Point B in a short time frame, and there’s only one man to do it. In 1977, it was Clint Eastwood in The Guantlet. In 2006, it was Bruce Willis in 16 Blocks. In 1975, it was Fred Williamson in his first (of five) turns as Jesse Crowder, a private investigator who used to be a cop but did things his way. The DA in New York reaches out to him and has him bring a mob accountant from L.A. to New York in 48 hours to testify.

Crowder hooks up with an attractive woman attached to the mob, and she gives him a gold watch to remember her by. Which we in the audience can already see is a plot device, but which Crowder never thinks of. Crowder goes to LA and picks up the schlub and then leads him via airplanes, trains, and buses to New York. The majority of the film is lingering shots, fisticuffs with the four bad guys on his tail (although there is some gunplay, most everyone in this film is a remarkably bad shot), confounding decisions, and Crowder getting laid with various women along the way.

Unfortunately, the film has some head-scratching decisions in it. Like, why does Crowder think that the DA has sent a woman to sleep with him who gives him a watch that he starts wearing, and when the bad guys find him at every stop along the way, he thinks someone is leaking his travel plans–until the end, when he discovers the watch has a homing device in it! Like why does he take trains and buses when he could fly? How did he make that cross-country trip in 2 days, and most of it was daylit? When he led the bad guys off and they just left their car to chase him, when he gets back to the road, why does he not take the car or disable it, resulting in them arriving at his next station just as Crowder and the accountant do?

But I guess most people were there to see Fred Williamson doing his thing. And do his thing he would: He appeared in four more films as Jesse Crowder.

I mentioned Get Christie Love! (1974) at the outset of this running log of the films in this set as I bought a DVD containing the television movie which served as the pilot for the short-lived television series of the same name back when I lived in Casinoport and the local grocery store had these “old” movies for a buck. I don’t know if I watched it in Casinoport, Old Trees, or at Nogglestead, but I did watch that DVD. And here it was as the last film on side 1 of disc 2.

I mentioned Get Christie Love! (1974) at the outset of this running log of the films in this set as I bought a DVD containing the television movie which served as the pilot for the short-lived television series of the same name back when I lived in Casinoport and the local grocery store had these “old” movies for a buck. I don’t know if I watched it in Casinoport, Old Trees, or at Nogglestead, but I did watch that DVD. And here it was as the last film on side 1 of disc 2.

In it, Teresa Graves plays Christie Love, a sassy, street-wise black detective on an all male, all white detective squad who starts the show by acting as a prostitute to catch a serial killer and then getting onto the real case: A local crime figure trafficking heroin has a ledger which details shipment and delivery details. Love follows the criminal’s girlfriend to Miami and back and tries to get her to open up and turn against the mobster, but the bad guy has a hold on her: her son. Who she claimed to have aborted. But it’s not really her son.

The narrative structure differs from a straight ahead film in that it has the little chapters that end with swelling music, a bit of a reveal or a cliffhanger, and then a commercial break (no commercials in the film, of course).

So the film has more of a television sensibility than a direct-to-video or direct-to-cable vibe that many of the other films in this set have.

The television show only lasted a year, and a single season means no syndication, so I never saw it in my youth.

Black Cobra (1987) stars Fred Williamson as Robert Malone, a cop who is akin to Dirty Harry but not as talkative. When a fashion photographer stumbles upon a motorcycle gang committing a murder, she breaks free from the leader of the gang by taking his picture and setting off the flash several times in his face. While he was wearing sunglasses. At night. So the bike gang, wanted for various crimes, wants her dead.

Black Cobra (1987) stars Fred Williamson as Robert Malone, a cop who is akin to Dirty Harry but not as talkative. When a fashion photographer stumbles upon a motorcycle gang committing a murder, she breaks free from the leader of the gang by taking his picture and setting off the flash several times in his face. While he was wearing sunglasses. At night. So the bike gang, wanted for various crimes, wants her dead.

And Malone needs to protect her.

The film is a series of set pieces where Malone gets closer to the identity of the gang and then a violent response followed by a little coda where the leader of the gang wasn’t dead!

Basically, enough material for a long television episode padded with some lingering shots, again generally of vehicles in motion (a shot of the bike gang getting on their bikes in the warehouse and then riding out took several seconds and added nothing but several seconds).

As I was watching, I thought maybe the lips weren’t matching up with the action–and since this film comes from Italy (and IMDB says Fred Williamson speaks Italian fluently), I thought perhaps it was dubbed into English. But IMDB’s entry for the film says its language is English (but the title is in Italian, so who knows? Well, someone does, but I’m not researching beyond Wikipedia and IMDB for a quick paragraph or two for a blog). Wait, I lied: I just clicked a link in the Wikipedia entry for the series (the films do not have their own entries), and the review says it’s dubbed. Which is what I thought, and why Williamson speaks fluent Italian.

At any rate, it’s not a Spaghetti Blaxploitation film, either, as it’s more in the mold of an 80s action film, and the look and feel of this film is definitely 80s. Great stylistic changes took place over the course of the decade between Death Journey and this movie. More than one. That’s kind of how it was before the Internet froze us all in amber in 2003.

Black Cobra 2 (1989) finds Williamson back as Bob Malone, Chicago cop. After a violent takedown of criminals, his captain sends him to the Philipines as part of an Interpol exchange. When Malone lands in Manila, he is pickpocketed by a talkative man in a white suit who also steals a briefcase and is pursued by armed men out of the airport. The pickpocket checks the briefcase and mails the claim ticket to his daughter.

Black Cobra 2 (1989) finds Williamson back as Bob Malone, Chicago cop. After a violent takedown of criminals, his captain sends him to the Philipines as part of an Interpol exchange. When Malone lands in Manila, he is pickpocketed by a talkative man in a white suit who also steals a briefcase and is pursued by armed men out of the airport. The pickpocket checks the briefcase and mails the claim ticket to his daughter.

Malone meets his counterpart who will be his partner for this movie, an Interpol agent played by Nicholas Hammond, the original Spider-Man. They find the pickpocket murdered, meet up with the daughter and try to discover who killed the pickpocket and what they were looking for. It leads to a visit to the dockyards, fights in a warehouse, and an assault on a terrorist base with lots of shooting from the hip in that 80s fashion.

The film makers had more budget with this film, as they have lots of shots of Chicago and then what I presume are Manila, but it’s probable that most of it was shot on set and in Italy.

Also, Malone is a different character in this film. Instead of the stoic and withdrawn character he was in the first, in this one he’s more of a typical tough buddy cop. So he’s switched archetypes.

So a rather generic direct-to-cable quality actioner with Fred Williamson. Which might have been a draw.

Black Cobra 3: The Manila Connection (1989). Wait a minute–this one is subtitled The Manila Connection? They were just in Manila last movie! I guess the production company had shots they wanted to use, so back to Manila Malone goes, this time at the behest of Interpol and the State Department to partner with a different Interpol agent, the grown-up child of an old war buddy.

Black Cobra 3: The Manila Connection (1989). Wait a minute–this one is subtitled The Manila Connection? They were just in Manila last movie! I guess the production company had shots they wanted to use, so back to Manila Malone goes, this time at the behest of Interpol and the State Department to partner with a different Interpol agent, the grown-up child of an old war buddy.

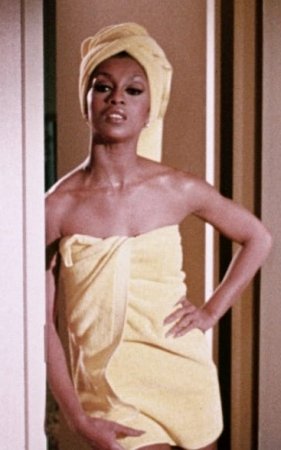

The film starts with a man infiltrating a military installation and finding…something. After a running gunfight through the forest jungle, he shows up at the home of a woman in the shower who throws on a towel and answers the door. He dies on her floor, and his body is later found in a local river.

Malone, as I mentioned, comes back to Manila to help the Interpol agent investigate as they suspect someone on the cross-agency team is on the take, and Malone is the only one Duncan, the adult son of Malone’s war buddy, can trust. They investigate in a series of set pieces, including a visit to the dockyards, fights in a warehouse, and an assault on a terrorist base with lots of shooting from the hip in that 80s fashion. It’s a little different as they have to walk into the jungle with their weapons and satchels (not backpacks–they carry their equipment in one hand, gym-bag style, presumably for hours).

Again, there’s a lot of extraneous motion shots–driving in the jungle by scenic waterfalls and a spot where Duncan and Malone enter a bazaar, and Malone says, “Now what?” and Duncan says, “It’s over there and to the left,” and then they walk in that direction. Some of the dialog is a little clunky, a little too much talking without reason, and whatnot. And Williamson plays Malone unevenly–sometimes he’s the dead serious menace, sometimes he’s the jokey buddy cop. I don’t wonder if Black Cobra 2 and Black Cobra 3 were shot simultaneously.

This is not the last film in the series–there is a Black Cobra 4–but it was the last film on the set, so I guess I won’t ever see the last of them. But I probably won’t see the last 4 Jesse Crowder films, either.

So for two weeks, I didn’t have to pick a film to watch at night–I just watched the next film on the set, which took a load off of my indecisive mind (to quote Twain: “I must have a prodigious amount of mind; it takes me as much as a week, sometimes, to make it up!”).

I found the films made it easier to relate to members of another race (more than message-based “theater” for sure). The black protagonists of these films except for The Final Comedown are relatable, at least as cinematic hero archetypes. Of course, it might help that I lived in the housing projects in the 1970s, surrounded by blacks who were my peers. But I sometimes wonder if the 1970s and 1980s were the high water mark of race relations in the United States, after the tumultuous 60s and before the establishment of the grievance industry in the 1990s.

I am not sure if I would recommend any of them as a stand-alone film, though. The quality of each is direct-to-video or direct-to-cable–but many of them came out before cable and video were big enough to warrant it–which meant that they got some cinematic release in the small theaters of the time. Many of them came out before Jaws and the advent of the blockbuster. It really was a different time.