After watching Hercules Unchained, I decided to go right to the source material. Well, Hercules Unchained is based Sophocles and Aeschylus’ works, not Euripides. Which becomes clear when one reads the tragedy Heracles that is included.

After watching Hercules Unchained, I decided to go right to the source material. Well, Hercules Unchained is based Sophocles and Aeschylus’ works, not Euripides. Which becomes clear when one reads the tragedy Heracles that is included.

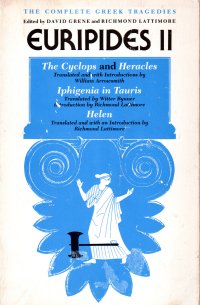

The book includes:

- The Cyclops, a comedy of sorts of a type called by scholars a satyr-play, so it’s a touch raunchy and one expects the chorus to be a bunch of men in goatskin pants and priapi (I hope I spelled that correctly; you will forgive me that I did not conduct an Internet search to make sure.) (I am just kidding; I do have a dictionary, so it is spelled correctly). It recounts Odysseus’ trip to the island of Polyphemus and the escape.

- Heracles, a tragedy that recounts Heracles’ return to Thebes, his madness, and its consequences.

- Iphegenia in Tauris, wherein Orestes goes to Tauris to steal back the idol of Artemis to calm the Furies chasing him, where Iphegenia is the high priestess after Artemis whisked her away from Agammemnon’s sacrifice.

- Helen, wherein Menelaus is shipwrecked in Egypt, where he finds the real Helen, not the fake Helen who was carried away by Paris, triggering the Trojan War.

You know, the contemporary wailing about Hollywood relying heavily on known intellectual properties for entertainment, but it has nothing on the ancient Greeks.

Euripedes put his own spin on the latter two tales, wherein both women were not where common (Homeric) stories had them. Artemis replaces Iphegenia with a hind during the moment of sacrifice, so Iphegenia is still alive after the Illiad. The gods make a double for Helen who is carried to Troy, so the real Helen has remained true to her husband. Given that the book is titled Euripedes II: Four Tragedies, I expected the stage to be littered with corpses at the end of these plays, but I was pleased that they ended a little more happily than that.

Each play has a relatively length bit of criticism/history/relating the stories to other Greek works that I skipped. A lot of times, I’ll come back and read the commentary after I read the source material, but this time I skipped most of it (I read the intro to Helen which is presented after the play and I read a little of the introduction to The Cyclops). I’m more interested in the source materials than the academic scholarship around it anyway.

At any rate, I flagged a couple of things:

- From Heracles, a defense of monotheism:

Ah, all this has no bearing on my grief;

but I do no believe the gods commit

adultery, or bind each other in chains.

I never did believe it; I never shalll

nor that one true god is tyrant of the rest.

If god is truly god, he is perfect,

lacking nothing. These are poets’ wretched lies. - In Iphegenia in Tauris, Iphegenia tips the forty for her presumed dead brother Orestes:

Give me the urn o gold which heavy holds

My tribute to the God of Death.

Orestes, son of Agammemnon, who

Who are lying under the dark earth, I lift

And pour–for you. - Also in Iphegenia in Tauris, Artemis herself lays down the baseball rule that the tie goes to the runner:

Orestes, once I saved you

When I was arbiter on Ares’ hill

And broke the tie by voting in your favor.

Now let it be the law that one who earns

An evenly divided verdict wins

His case.Note that in modern American civics, though, an evenly divided jury is hung, and in the Senate, the vice-president gets to vote to break the tie.

- From Helen, a brief aphorism that comes at the end of a speech that, erm, prophecies Luther’s arguments against some practices of the medieval church:

The best prophet is common sense, our native wit.

Oh, right, I cannot make that assertion about Luther and not give the wider context:

It shall be done, my lord.

Only, now I am sure

how rotten this business of prophets is, how full of lies,

There never was any good in burning things on fires

nor in the voices of fowl. It is sheer idiocy

even to think that birs do people any good.

Calchas said nothing about this, he never told

the army when he saw his friends die for a cloud,

nor Helenus either, and a city was stormed in vain.

You might say: “No, for God did not wish it that way.”

Then why consult the prophets? We should sacrifice

to the gods, ask them for blessings, and let prophecy go.

The art was invented as a bait for making money,

but no man ever got rich on magic without work.

The best prophet is common sense, our native wit.So you can see where I might have thought that: Luther was against some of the money-earning practices of the church, including the saying of masses with no attendees for money to expedite the stay in purgatory for dead relatives. So, basically, the criticism of the church is similar across time and churches.

Also, it gives a nice aphorism.

If you’re interested, you don’t have to buy the book; you can find all of these plays and more on MIT’s Classic page for Euripedes. You might like that, gentle reader, but as you know, I need a book. This book is part of a series, but I am not going to seek them out. But if I see them at ABC Books or the Friends of the Springfield-Greene County Library, I will be all on them.

Because these pieces of classical literature, in good translations, are very approachable and readable especially if you skip the academic and mostly irrelevant prose bookending them.